Mike Metty ’64 had just finished up his doctorate in higher education at Syracuse University in the spring of 1969 when he got an offer he couldn’t refuse. Morris Keeton, the vice president of Antioch College in Ohio, was on the phone asking if Metty would like to help set up a new college campus in a new town called Columbia, Maryland. Well, yes, he would. Here was a dream opportunity. A chance to test every theory he’d ever had about improving American higher ed.

In the early-1960s, the real estate developer Jim Rouse began quietly buying up parcels of land in Maryland’s Howard County, a mostly rural area strategically located between Baltimore and Washington. Once he had assembled a critical mass of properties, Rouse announced that he was going to create a planned city he called Columbia. Among his many plans for the new town was an experimental school, and so he reached out to Ohio’s Antioch College, because, says Metty, “he admired the liberal work/study perspective they brought to higher ed.”

Keeton was enthusiastic, and so was Jim Dixon ’39, Antioch’s president, but they needed someone familiar with both the Antioch model and with the cutting-edge ideas in higher ed, someone without any other current commitments. That was the recently graduated Metty. As an undergrad, he’d been Keeton’s student at Yellow Springs, and as a grad student, he’d been Keeton’s research assistant when the latter was a visiting professor at Syracuse.

“It was an interesting challenge for Yellow Springs,” Metty says today from his home on Florida’s Gulf Coast. “How do you look at other locations as a way to experiment on new ways to deliver an educational opportunity? It was never the intention to replicate the Yellow Springs campus; it was always a way to engage different communities with a different kind of education. I had a lot of ideas about how colleges might better serve their communities.

“Some of those ideas were rooted in the Yellow Springs model: work as a part of learning, smaller community, smaller classes, a community that governed itself, faculty that had expertise in their arena but also strongly interested in teaching as well as research. But I wanted to go beyond that. I thought that the curriculum had to be designed by the student. The student I was most interested in was fully capable of designing their study as long as they had support of the faculty. I felt it was a principle worth testing.”

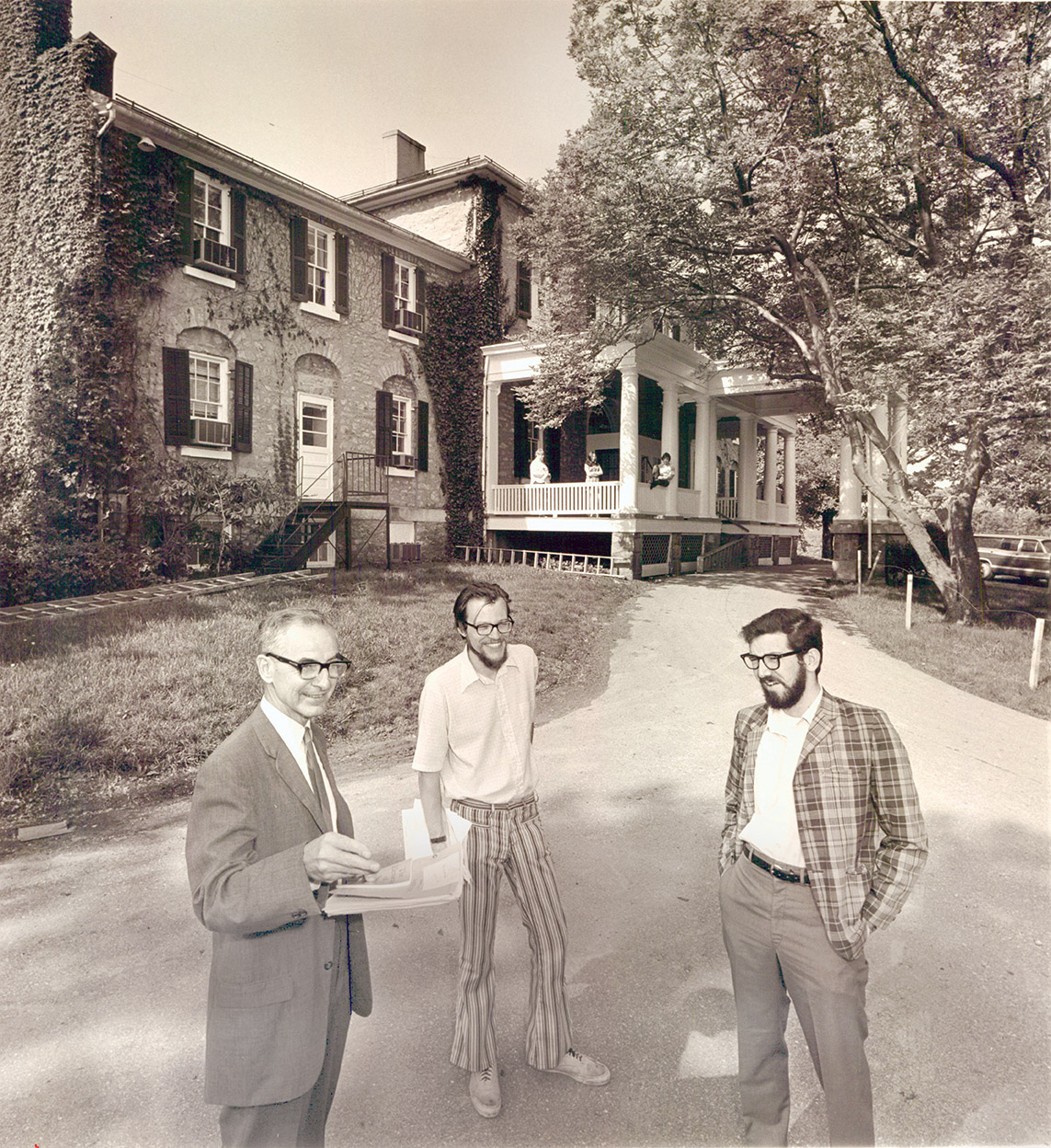

Metty arrived in Maryland as a tall, rail-thin 27-year-old, with a hint of whiskers on his chin. He was confronted by a planned city that was still more plan than city. Columbia had some man-made lakes, a summer home for the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, a Frank Gehry-designed Rouse Company Building and a few scattered housing clusters and village centers. But most of the town was still woods and muddy fields where the planned mall, office buildings and housing were meant to go. Metty, Keeton, fellow Syracuse transplant Steve Plumer and Yellow Springs refugee Judson Jerome set up offices in the Columbia Manor, a pre-Rouse mansion on a hill, to hire faculty and staff and to recruit students.

“The original plan was to spend a year planning the process,” Metty recalls, “but as we chewed on it, we decided, ‘Let’s involve students from day one. Let’s invite 10-15 students for whom creating a new educational institution would be an exciting project. Let’s get them involved from the beginning, so they’re a part of building it from the ground up.’ The consensus was not to have everything ready for them but to have them be part of the development. We had a place at the Manor, brought on a couple of faculty members quickly. Some Rouse Company planners got involved, and Morris was in and out.”

“I believed that if a student had significant control over their own future,” Metty explains, “it would increase their investment and would lead to independent human beings.”

Mike Metty

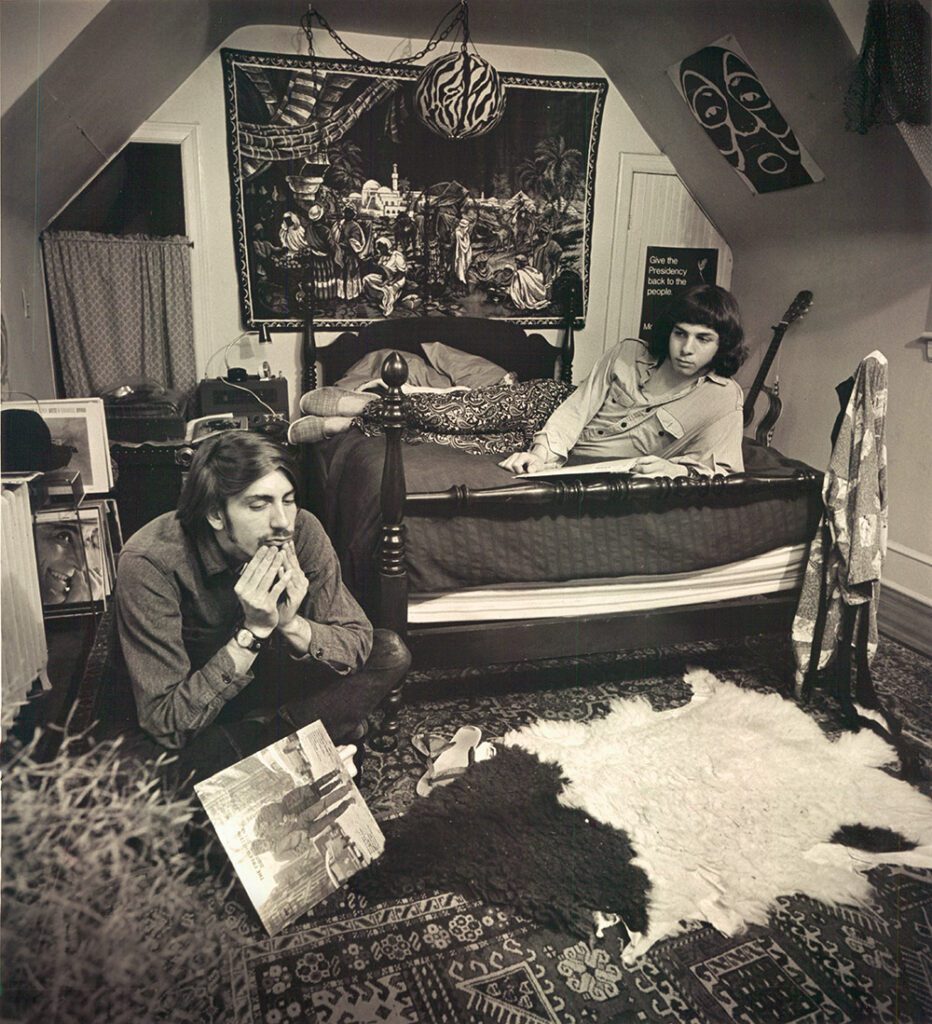

More than 50 students arrived that fall, and this writer was part of a second wave in February, adding up to nearly 100 in all. We showed up at the old stone manor house filled with ramshackle furniture and were expected to sink or swim. We were encouraged to find our own housing and transportation, to design our own independent studies, and to find a role in defining and governing the fledgling institution. We were charged at every turn with taking charge of our educations and lives.

“I believed that if a student had significant control over their own future,” Metty explains, “it would increase their investment and would lead to independent human beings. I felt if education was really to be lifelong learning as everyone said, it couldn’t be just talked about, it had to be done right from the start, so students could learn how to do it. There was too much narrowing of scope in students’ intellectual lives.

“At most schools, you had to take three courses from column A, five from column B and six from column C. You felt you had some choice, but the choices were prescribed. Yellow Springs had been pushing the envelope, but I felt we had to push much further. If you’re going to be an independent human being, you have to make decisions and live with the consequences; without that, everything else was fake.”

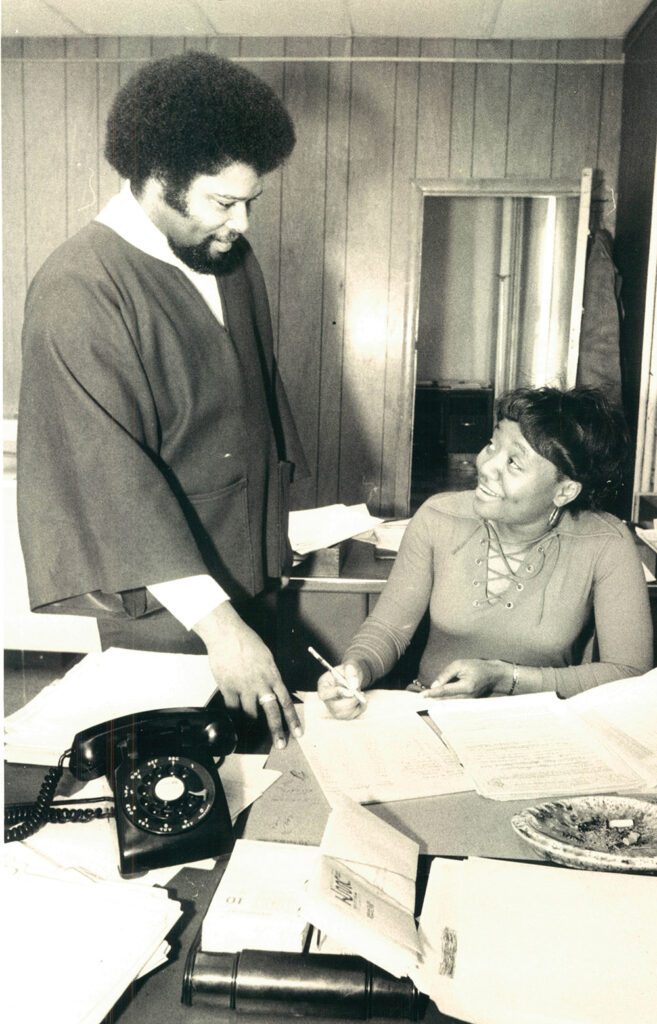

It was an exciting first year, but Metty, Keeton, Plumer, and new hire Al Engelman had another item on their agenda. The suburban feel of the Columbia center had attracted a mostly young and white student body, not so different from Yellow Springs, and the new Washington center had attracted a mostly older African-American student body. Metty and his colleagues wanted to combine the two demographics in a third center in Baltimore, which opened in the fall of 1970.

“We had to see if such an institution could work in an urban environment if it took on a different kind of student,” Metty explains. The staff had recruited a few dozen African-American paraprofessionals who were working in college-level jobs without the credential that could give them the pay they deserved. These were joined by the Columbia students and newcomers just

like them.

“A mix of students like that–young students who are bright as hell but haven’t had much experience and people who are battle-tested–that can be a rich environment,” Metty still argues. “When I was in Yellow Springs, Coretta Scott King (’51) would come through every few years to talk to students, and some of us would go off and work with Dr. King on various projects. That got me thinking, ‘How can we bring together students from different races, different economic backgrounds in a pressure-cooker environment to see how they work together?’

“Sometimes it worked quite well, and sometimes the shit hit the fan. But as a whole, I felt the venture in building a community, the venture in bumping heads, was productive. Neither group would have gotten that experience any other way.”

The African-American students included Paul Coates ’79 (founder of Black Classic Press and the father of Ta-Nehisi Coates), Hattie Harrison ’79 (future Maryland state delegate), Ruby Glover ’78 (jazz singer and promoter) and Charlie Simmons ’70 (founder of Sojourner-Douglass College). The European-American students included John Doe ’75 (co-founder of the rock band X), Franz Lidz ’73 (Sports Illustrated staff writer), Deirdre O’Connell ’76 (stage/film actress, e.g. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind) and Billy Russell ’77, ’79 (co-founder of the Grassroots Crisis Intervention Center).

Antioch Maryland was easy to get into, but hard to get out of. If you found this unusual education attractive, you could probably come. To graduate, though, you had to survive and master real-world jobs; you had to define in your own words what you learned (in or out of a classroom), and you had to force the institution to give you what you wanted. A lot of people wasted a lot of time and money at Antioch, but those who graduated came away with one of the most practical educations around.

“I had been in several colleges before I came to Antioch,” explains Maggie Rice ’72, who went on to manage a Chicago theater and to launch her own financial-advisor business in Denver, “but this was the first one that said, ʻGo out and try things, and if you get into trouble, we’ll come along and bail you out.ʼ They gave me the confidence that I could actually do things, and that made all the difference in the world.”

“Back in the ʼ60s, there was this tremendous energy to explore and challenge things,” recalls Paul Bartlett ’74, who now owns his own food-consulting company in Baltimore, “and there was nowhere to turn that energy except to getting in trouble. Antioch was the one place that channeled that energy into something constructive. Every other college I’d been to wanted you to follow their agenda. Antioch had an open agenda.”

“Other colleges I had been to kept you insulated from the real world,” adds Ed Fegreus ’72, who now has his own law practice in Boston, “but Antioch forced you to come to terms with the way the world really worked. When I graduated, I hadn’t read everything that people from other colleges had read, but I knew how things got done in the real world and I knew how to get my hands on the information I had missed out on. I had no problem at Harvard.”

With their training in irreverence and project creation, it’s not surprising that many Antioch-Maryland graduates have worked for themselves as freelance writers, freelance radio producers, stage-crew contractors, video producers, sheep farmers, house builders, tap dancers and so on. Even those who worked for large institutions (the U.S. Departments of Energy and Defense, the Honeywell Corporation, Towson State University, the Chicago City Government, National Public Radio) carved out their own niches within the bureaucracy.

Those students who weren’t disciplined enough and confident enough to handle a self-directed education often fell to the wayside and suffered as a result. The balancing act between freedom and safety is a tricky one, and Antioch Maryland didn’t always find the right balance.

“Personally I could not have asked for a better environment for myself,” says Ric Moore ’72, a self-described “subversive bureaucrat” in the federal government, “but I know it got others side-tracked. If you didn’t have the necessary self-motivation, gumption, self-discipline, creativity, and an unorthodox attitude, you could get left in the lurch. But then, every place is that way. I don’t think any one model works for everyone. There need to be more options, but with better ways of finding your way through the labyrinth. I have no idea how I figured out what would ‘work’ for me, except that the penalties for dropping out back then seemed much less drastic and final than they do these days.”

“Did it fuck up sometimes? Absolutely,” Metty admits. “But as I visit with students since then, I found that the experience worked for them and helped them develop into competent individuals in charge of their own lives. I also recognize that some people didn’t have a good experience and left, disappeared or fell through the cracks. I think the opportunity to be in control of your education is important, but we have to have better processes in place and be willing to intervene when students are failing. But how to do that without becoming dominating is a difficult line to walk. We wrestle with this whole issue of paternalism in education, and we don’t do a good job with it.”

The Baltimore, Columbia and Washington centers began with support from the Yellow Springs administration, but opposition soon emerged among the Ohio faculty and trustees. The Maryland administration was often overly optimistic about how many students were coming, and when they didn’t arrive, that created budget deficits. Philosophical and financial conflicts widened a gap that no one knew how to bridge.

“Our relations with Yellow Springs deteriorated,” says Metty of the mid-’70s, “and I suspect both sides contributed to it. Yellow Springs was going through some severe financial management issues of its own. The faculty were becoming more conservative; tolerance for risk was diminishing. We weren’t wise enough to understand that and figure out what to do about it. Yellow Springs was imploding, and the outlying places probably added to that.

“I had a foot in both camps, having graduated from Yellow Springs while being a strong proponent of centers doing different things around the country. I did my best to maintain my relationships in Yellow Springs, but I don’t know if I succeeded. The system wasn’t designed well to manage all these different enterprises.”

The Baltimore, Columbia and Washington centers were forced to close down in 1983. The network campuses that survived were almost all graduate programs, and Metty sees that as a crucial distinction.

“Graduate programs for the most part are very outcome-driven,” he points out, “and that establishes a much clearer goal set. Undergraduate programs, by contrast, are mostly dealing with the personal, emotional, and educational development of young folks who aren’t as experienced or goal-directed. So it’s a broader array of things that have to be delivered and sustained. So, yes, graduate programs are easier to run than undergraduate programs.”

After the centers closed, Metty moved to Alaska, where he spent 15 years developing new educational programs for indigenous Alaskans. He eventually moved on to administer programs in continuing and technical education in Nevada, California, and Michigan. Now 76, he’s retired to Tarpon Springs, Florida, where he volunteers for various community organizations. But he looks back on his 14 years at Antioch Maryland with unapologetic pride.

Much of my time post-Antioch has been spent in public institutions,” Metty summarizes, “which have great value in the breadth of who they can serve and what they can provide. But there are many more constraints on what they can do, and sometimes those boundaries are too restrictive for students, what they want and what they need. Most institutions are there to maintain the status quo and not enough are challenging it.

“It’s harder and harder to find a college that has a divergent strategy, like we had at Antioch in Maryland—not impossible, but much harder. Those are difficult institutions to manage, especially as dollars become more difficult to come by and as the measures of success become narrower. The cost of that is a lot of people get left behind. We gain more from divergent thinking than convergent thinking, more from divergent institutions than convergent institutions.”