The same passion that drew Mary Lou Finley to Chicago during the civil rights era led her down the path to teaching social justice.

Finley, PhD, sociologist, and Professor Emerita at Antioch University Seattle, was an undergraduate student at Stanford University in 1965 when she learned about a student recruitment effort of volunteers to work for a movement in one of the most racially segregated cities in the country. Known as the Chicago Freedom Movement, it was meant to combat discriminatory real estate practices that kept blacks inside big city ghettos, often in severely dilapidated housing.

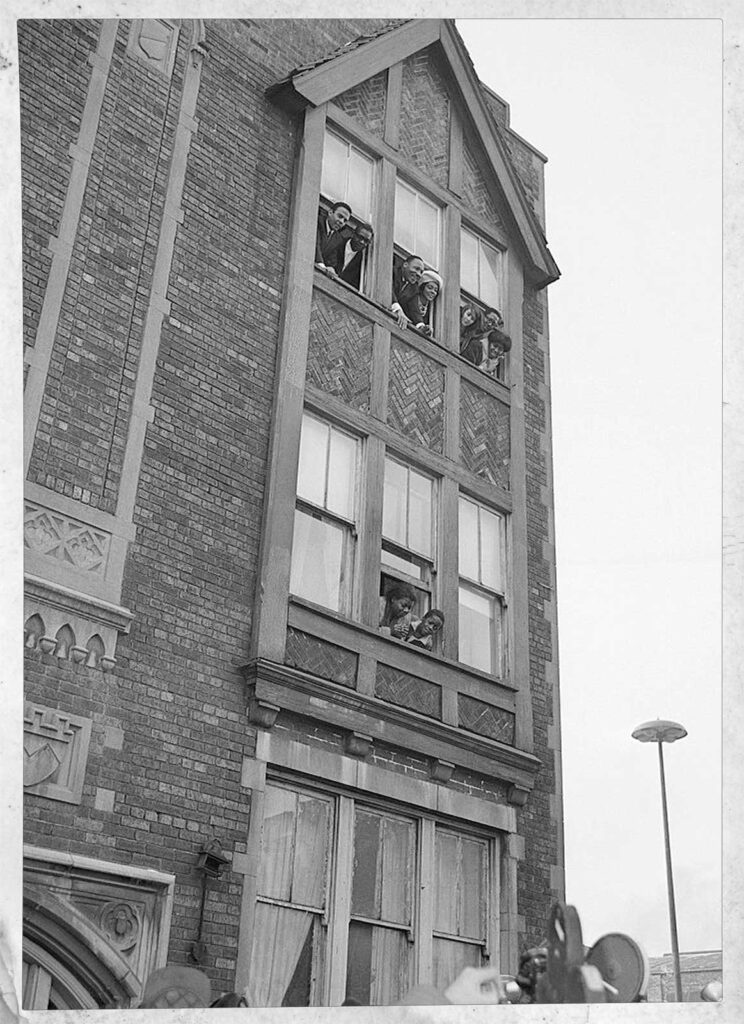

She moved to Chicago that summer and was soon invited to join the staff of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference-Chicago Project . There she lived and worked out of a church parish on Chicago’s West Side, and served as secretary to Project Director James Bevel, a minister who worked closely with Dr. King in Selma, Birmingham, and other Southern campaigns.

When King arrived in Chicago the following winter of 1966, he needed a base from which to work on housing issues, so he chose an apartment in the middle of Lawndale, one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in the city.

Finley and other volunteers helped the family with whatever they needed, which included cleaning, searching for second-hand furniture, and bringing ribs.

“I was told Dr. King liked ribs when starting a movement,” Finley says, who sat on the floor and ate with him that day. She also helped bring them blankets because it was the dead of winter when they moved in and the heat to the apartment was shut off at night.

She remembers Dr. King as “very sweet and quiet” and “a good listener.”

I feel I was given a gift.

Mary Lou Finley

He was such a good listener he befriended members of the local gang, the Vice Lords, who served as security for him and visited him at his apartment often during the six months he lived in Chicago.

“If he’d stayed in a hotel downtown, none of this would have happened. I was in the middle of everything. I feel I was given a gift,” she says.

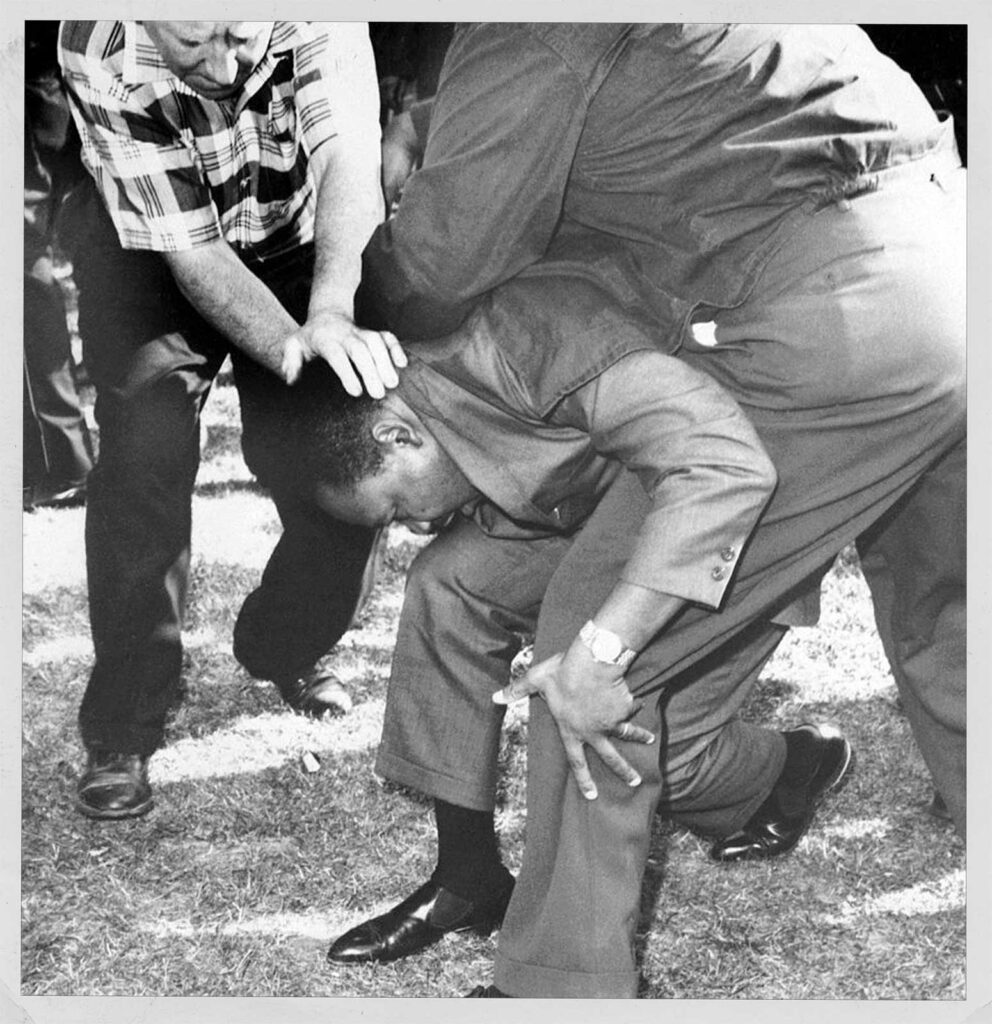

During that summer King’s campaign was his first major one outside the Deep South. It culminated with demonstrations and marches into all-white neighborhoods to end housing segregation, most famously during a march in Marquette Park where Dr. King was attacked by an angry mob.

The tenant unions King helped organize paved the way for an improvement in tenant rights across the nation. Most importantly, the movement led to the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968—signed into law a week after Dr. King’s assassination in 1968.

The building Dr. King made his Chicago home was torn down to a pile of bricks before it was recently rebuilt as a low-income housing unit for 40 families. In one corner of the building is the MLK Fair Housing Exhibit Center that tells the story of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Chicago Freedom Movement.

When she arrived to teach at Antioch in the early ‘80s, Finley thought back on the work that still needed to be done.

“I felt in some ways I never left Chicago,” she says. “Even though the movement changed and moved on in many ways, there are still discrimination issues, and poverty is at least as bad as it was in the 1960s. Poverty remains the movement’s great unfinished work.”

When Dr. King was jailed in Birmingham, Alabama, he wrote, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“That’s the kind of feeling I had when I was in the movement,” Finley says.

Finley’s experiences in Chicago in the 1960s informed her interests teaching sociology and public health at Antioch, in which she focused a lens on such areas as poverty, race, class, and gender studies and health issues in developing countries.

In 2004, she re-connected with Chicago Freedom Movement colleague Dr. Bernard LaFayette, later appointed by Dr. King as national coordinator of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign.

LaFayette invited her to help organize a 40th anniversary celebration of Dr. King’s work in Chicago that was to happen two years later.

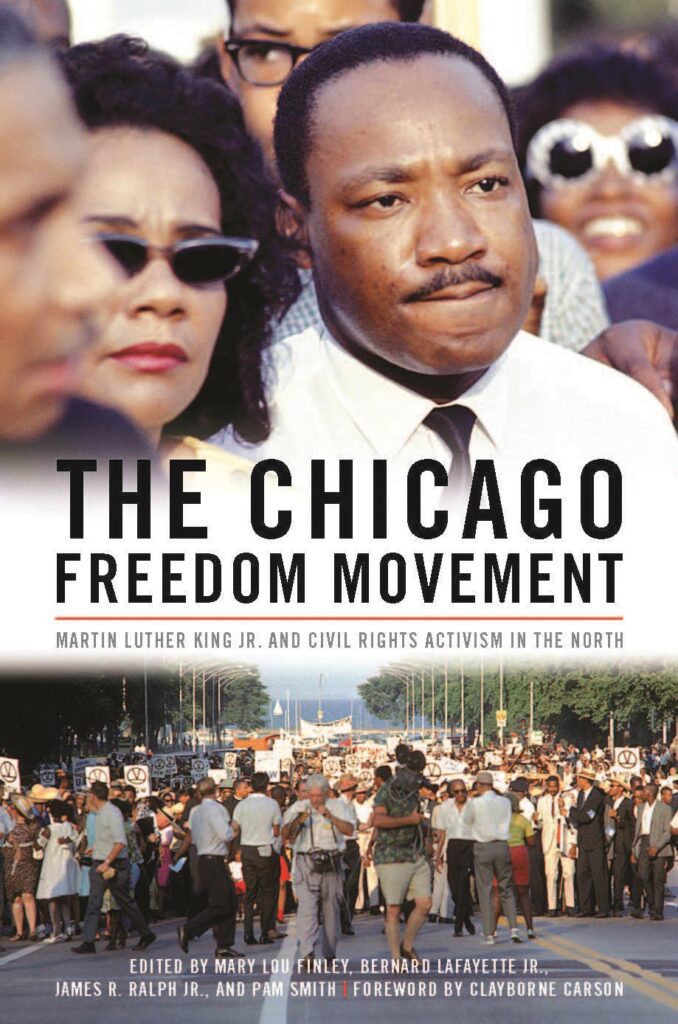

That same year she began work as co-editor of the book, The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North, along with LaFayette and 20 other contributors. The book was published in 2016, on the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s work in Chicago. She also became a certified Kingian Nonviolence trainer, and in 2016 co-founded the Addie Wyatt Center for Nonviolence Training in Chicago with three Chicago colleagues.

Finley’s own work from her time in Chicago continued when she began taking Antioch students with her on the annual Historical and Educational Civil Rights Tour, led by Dr. Bernard LaFayette and Charles Alphin, DDK Tours, and co-hosted by the Ira and Mary Zepp Center for Nonviolence and Peace Education.

One of those students, Michaella Ibambasi-Marebe, attended the tour with Finley in January 2019. She came to Seattle from Rwanda five years ago and is studying for her bachelor’s in health and psychology with a particular interest in mental health care and awareness.

She was struck by an exhibit at the Legacy Museum in which visitors can sit in a booth in a makeshift prison and listen on the phone through plexiglass to the stories of prisoners.

“One innocent man in his 70s had been incarcerated for decades,” she says. “It reminded me of my grandfather, a Tutsi who was accused of being a spy and was tortured to death in prison. There’s a similarity in all the injustices; a misunderstanding and hatred that stems from different reasons. Because someone doesn’t look like you they were robbed of the life they deserved.”

On the tour she also learned about Ida B. Wells, a former slave who became an activist and journalist and one of the most influential women in history.

“Seeing her work, dedication, and independence was inspiring. Even with all the hard things, people still moved through life with a lot of strength and lack of fear,” she says.

…even if you don’t have anything, you can still have a glimmer of hope and a voice.

Mary Lou Finley

Another student, Isabell Boyd, also attended the tour. She said her experiences helped her turn her anger into a passion to serve youth. She works as an instructional assistant and intervention specialist in the Seattle public school system and plans to pursue her master’s in education.

One of her personal highlights of the 2019 tour was a visit to The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery, Alabama, which displays the history of slavery and racism in America.

“It focused on the school-to-prison pipeline,” she says. “Reading the stories of these young men reminded me of my own son and made me wonder where our future is headed with our young black men.”

She was especially moved by the people of Marks, Mississippi, where the Poor People’s Campaign, or Poor People’s March on Washington began in 1968. Organized by Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the campaign was an effort to gain economic justice for poor people in the U.S.

The town was poverty-stricken and its school system was failing. Yet people who had left had now returned and were leading a grassroots effort to rebuild their community, which included building housing for teachers who have been difficult to retain.

“They believe education is a tool out of poverty,” Boyd says. “Even if you don’t have anything, you can still have a glimmer of hope and a voice.”

The tour inspired her to provide more leadership opportunities in her own classroom and implement civil rights history into her lesson planning.

At the Legacy Museum she learned about the Birmingham Children’s Crusade of 1963, a pivotal event in the civil rights movement when young people became activists.

“Children are more capable than we think. We’re not giving them opportunities to have a voice,” Boyd says. “We need to invest in our youth.”

For more information on the 2020 Civil Rights tour, email Dr. Finley at [email protected].