Wendy Ortiz came to Antioch as a young person with an important story to excavate. She found literary mentorship, a psychology career, and even lifelong partnership. But that doesn’t mean the rest has been simple.

If you visit the campus of Antioch Los Angeles, you should take the chance to visit a literary artifact. Ride the elevator to the fourth floor and walk down the hall, past the library and learning center and computer lab, to the offices of the MFA in Creative Writing. Turn left, and in the far corner you will find a tall bookcase with locked glass doors. Look through the hundreds of black-spined books, scanning the silver lettering. You’ll recognize the names of prominent authors who graduated from the program. The title you want is this: “What Is and What Should Never Be – W. Ortiz.”

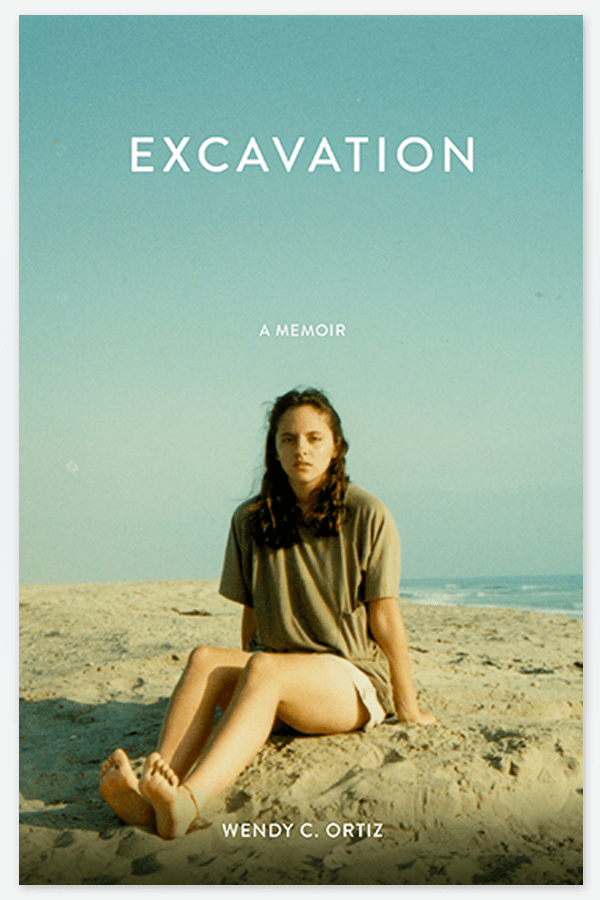

This is a copy of the master’s thesis of Wendy C. Ortiz ’02, ’10 (Antioch Los Angeles, MFA in Creative Writing, MA in Clinical Psychology), an early draft of the manuscript that would, after much revision, be published in 2014 as her memoir Excavation. In her book, Ortiz uncovers, or “excavates,” the hidden details of her adolescence, focusing on explosive material—her relationship with her middle school English teacher, who groomed and abused Ortiz beginning when she was thirteen. Yet the writing never strays into sensationalism. It is centered on the young Ortiz: a girl who, without much positive help, is exploring and discovering her sexuality, queerness, and writerly identity. It is a book of great, lasting power.

Over the years since Excavation came out, it has stayed in print and, largely through word of mouth, found many thousands of readers. Today it is recognized as a forerunner of the #MeToo movement. And through two follow-ups—2015’s Hollywood Notebook and her 2016 “dreamoir,” Bruja—Ortiz has built a body of work as one of our most inventive and important memoirists.

Even with the these creative successes, though, Ortiz has no assurance that her next book will be released by a major publisher. None of her previous ones were. And as a queer, Latinx writer, she is very aware of the ways that the publishing industry has been reluctant to give a platform to writers from her background—especially when their stories are complicated. Even as she works on a new memoir about anger and a heart condition, she has kept her day job as a psychotherapist. A few months ago, she took some time out of her busy schedule to talk about her career, her art, and the big role that Antioch has played in both.

Ortiz started writing her first novel in middle school, handwriting on hundreds of lined sheets of paper that she collected in a red three-ring binder. But a straight shot to a literary career was not in the cards for her.

As she neared the end of high school, she knew she would go to college—her parents had told her that from when she was a child—but there was little support in figuring out how. She spent two years at a community college in the San Fernando Valley, a few miles from where she grew up. It was only after a friend came back from a summer spent riding the rails in the Pacific Northwest that she heard of Evergreen State College. Her friend made it sound perfect for her: they didn’t require SAT’s, and classes were often experimental. She decided to apply.

At Evergreen, a public university in Olympia, Washington, Ortiz found her politics. “I ended up staying for eight years, which was far longer than I had ever imagined,” she explains. “I became a part of a community, and I did a lot of growing up there.”

In Olympia, she fell in and out of love, kept filling journals with her writing, and made friends who used art to celebrate diverse bodies in a way that helped her see her own beauty. She started reclaiming her Chicana identity—something her parents had deliberately withheld from her in an attempt to help her succeed in the U.S. (“They did not teach me Spanish,” says Ortiz. “They didn’t teach me much about Mexican culture.”)

During her last term at Evergreen, she took a creative writing class and reconnected with her passion for writing. After graduating from college, Ortiz published her writing by making zines—self-designed chapbooks printed on a copy machine and bound by hand. Her zine was called freefeeder, from the term cat people use to describe the practice of leaving the food bowl full at all times, so that their cat dictates their own diet. As she writes in the first issue, “I like the sound of the word, its alliteration. Its rhythmic quality. To a woman who has struggled with body image, the word sounded powerful.”

The zine’s first issue explores Ortiz’s relationship with her body, her history of diets and disordered eating, and also her family and cultural history of worrying about weight and disciplining the body. “I am a Chicana woman,” she writes, “which accounts for some of the other self-loathing things I have done to my body in an attempt to look like US teen angel snow white queen. That’s a whole other zine.”

Ortiz wrote, designed, and published three issues of freefeeder (you can read the first online) and shared them within her community. The zine found readers—and to Ortiz’s delight has even ended up, over two decades later, archived in several university libraries. But perhaps the most important thing it did was help her begin to find her voice.

The desire to sharpen this voice—and to possibly excavate more of the experiences of her childhood—is what brought her to study at the MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch Los Angeles. That, and she appreciated that the biannual residencies were in LA, a familiar place.

At the time, the program was still in its early years, chaired by its founder, the poet Eloise Klein Healy. Ortiz found it to be a very supportive community. “Everybody seemed very collaborative,” she says. “There was always a feeling of: this is not a competitive program. We’re not competing with each other. We’re trying to help each other all the time.”

For Ortiz, a major appeal of the program was the opportunity to focus on her identity as a writer. “It seemed like a way to give myself time and space to work on different projects that I had ideas about,” she says. “Including what would become Excavation.” She went deep into this work with mentors including Paul Lisicky, David Ulin, and Bernard Cooper.

By her final term, Ortiz had decided to move back to Los Angeles. And after graduating, she ended up staying at Antioch—first as the MFA’s temporary program coordinator and then, when the previous coordinator didn’t come back from maternity leave, permanent program coordinator.

During the time she held this job, Ortiz decided to enroll in another Antioch program: the MA in Clinical Psychology. She was realizing that supporting herself as a university admin wasn’t necessarily the life she wanted, and a former therapist had told her that, if she ever wanted to, she would make a great therapist herself. Ortiz told herself, “This could be a good career that I could do part time and still have time for my writing.” And, she says, “It was. It panned out. That’s what’s happened.”

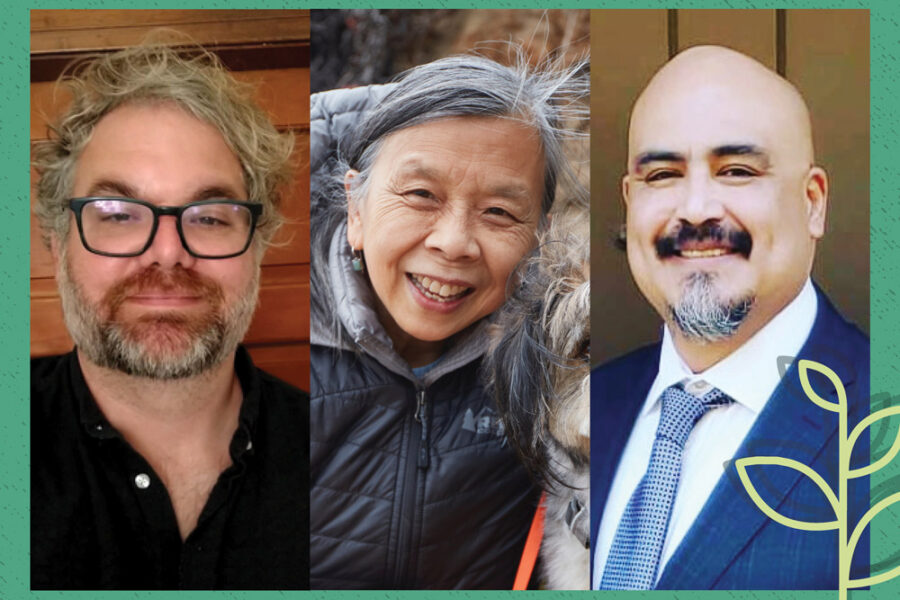

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Antioch is the place where Ortiz made the leap to being a professional writer as well as where she got the professional training and licensure for her day job as a therapist. There’s one more connection she made at Antioch worth mentioning, too. While working at Antioch, she became friends and then partners with Sandy Lee, now Chief Operations Officer of Antioch Los Angeles. They have a daughter together.

Ortiz graduated from the MFA in 2002, but it took over a decade to publish the manuscript that sits on the bookshelf in the MFA offices. In some part this is because it wasn’t done yet; she kept revising it over the following decade. But it’s also because when she tried to publish it, she encountered a publishing world uninterested in the memoir of a queer, Latinx woman exploring her abuse at the hands of a teacher.

Tales of teachers engaging in sexual misconduct with their underage students have been salacious tabloid fodder for generations, but in 2014, when Excavation finally did come out, it seems to have been the first English-language memoir of its kind. For Ortiz, this absence was part of why she wrote the book in the first place. “I would have wanted to come across that book,” she says, “because I looked for it for years, from the time I was 14.”

Unfortunately, when she tried to sell the manuscript, the publishing industry showed no interest in bringing her story to readers. She and her agent submitted it to editors at all the top publishing houses, and they all passed on it—often with nice notes. She gave up and only published it later, when an editor at a small press, Future Tense, reached out by email because he liked another piece she had written. To this day, Excavation has never been released by a publisher with a full-time publicity department. As much as it has been a word-of-mouth success—and it truly has been—it is hard not to think of how much more successful it could have been, if a mainstream publisher had championed it.

Perhaps if it had been published a few years later, the book’s reception would have been different. Excavation presaged the #MeToo movement and its disclosures of abuse by powerful men. It also paved the way for a host of books that use the tools of creative nonfiction in memoir, from Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House to Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s The Fact of a Body.

But for Ortiz, the feeling of being left on the sidelines only grew when, in early 2020, it was reported that the publisher William Morrow had paid over a million dollars for a novel telling what, from the synopsis, sounded like a nearly identical story to Ortiz’s own. The main differences were that the book was fictional—and was written by a white woman. It was slated to be an Oprah’s Book Club selection.

Ortiz chose to speak out on Twitter about the dynamics she saw in play: “can’t wait until February when a white woman’s book of fiction that sounds very much like Excavation is lauded, stephen king’s stamp of approval is touted, etc.”

She was speaking to a frustration that many writers of color have been pointing out in recent years: a dynamic where white writers receive enormous advances and institutional support for telling certain stories while writers of color telling those same stories are often shut out of the publishing world altogether. The canonical example is the attention and praise heaped on the novel American Dirt, a white woman’s sensationalist retelling of Mexican immigration to the U.S. That book’s selection for Oprah’s Book Club led the Latinx writers Myriam Gurba, David Bowles, and Roberto Lovato ’18 (Antioch Los Angeles, MFA in Creative Writing) to start the #DignidadLiteraria movement.

Ortiz’s critique was of the publishing industry at large, but many people instead heard that Ortiz was accusing the other writer of plagiarism. Controversy erupted, and many loudly argued that the other author hadn’t plagiarized—a defense that missed Ortiz’s point entirely. For Ortiz, the whole ordeal was frustrating. No one seemed interested in hearing what she was actually saying, despite the long essay she published in Gay Magazine about literary gatekeeping and her experience of being shut out. Instead, people heard what they wanted to hear, and they ascribed to her the worst motives. Ortiz soon faced an angry mob accusing her of trying to ruin this other writer’s career. (The other writer had pocketed a seven-figure advance; the novel was a massive bestseller despite Oprah’s Book Club rescinding its selection.)

For Ortiz, the only path forward was to quiet down and wait for the controversy to blow over. And to get off social media. “I basically feel like anybody who’s on social media is gonna go through this at some point in time,” she says. “If they are ever honest.”

In place of stirring up hornet’s nests on social media, Ortiz has been saving up her honesty for her own writing. She’s in the middle of writing her latest book, Subversive Heart, a blend of memoir and what she calls autoethnography that closely examines the experience of atrial fibrillation—a medical condition that Ortiz was recently was diagnosed with—to consider both the forces that have shaped her politically and her relationship with anger.

“It’s super different than Excavation,” she explains. “It’s not focused on a trauma. Certainly trauma stories are in the book, but that’s not the focus of the book. The focus is anger… and the other focus is the heart, and what an emotion like anger can potentially do, especially when it’s not metabolized.”

It sounds like a big, potentially overwhelming subject. But of course Ortiz approaches it with her characteristic matter-of-factness and focus on embodied experience. A recent excerpt published in the online literary magazine Joyland is at turns funny and meditative. It ends with a passage that reflects the heart’s work but also Ortiz’s work as a writer. She writes: “I pause and listen: my heart is quiet. It’s doing the thing I remember, the thing it did before all of this started; it’s silently, assuredly, quietly, working.”