The activist, scholar, teacher, and healer Claudia Ford is using her specific background to ask the biggest questions there are.

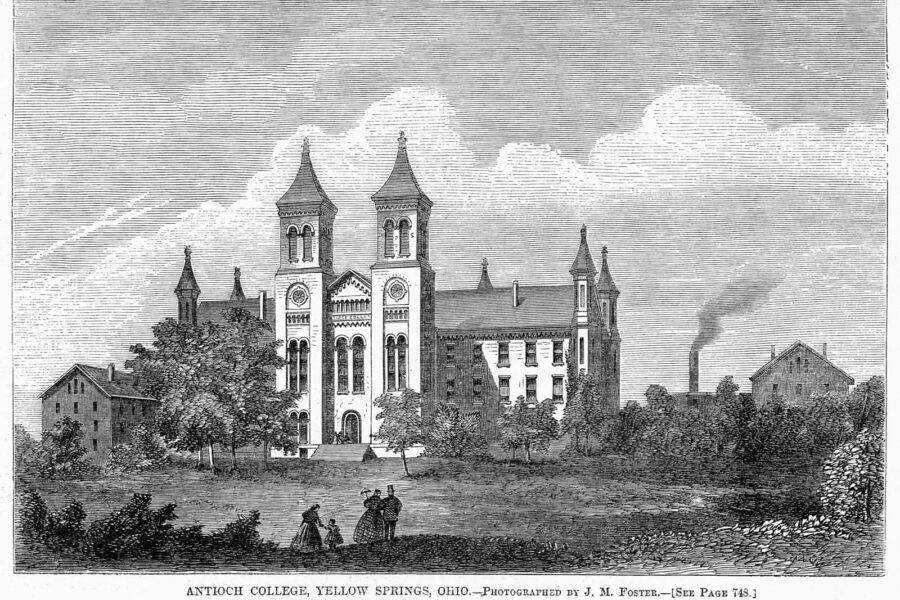

I call Claudia J. Ford ’86, ’15 (Antioch College, MBA in Health Administration and Antioch New England, PhD in Environmental Studies) on a weekday morning. The first thing that strikes me is the calm, silky timbre of her voice. Just as we start talking, she warns me: she’s waiting for a knock on the door. One of her sons has ordered dinner for her to be delivered. The time difference is because she is in Germany for a semester-long fellowship at the Justus Liebig University in Giessen. She’s there to study some of the world’s biggest philosophical questions: What does it mean that we humans and the other parts of our world are all, at our deepest essence, made of stardust? How can we exist sustainably with the other parts of Earth? Her project is titled, “What Earth is Made of: Planetary Materials, Indigenous Knowledge, and the Gaia Hypothesis.”

Ford isn’t as intimidating as these big questions might make her sound. The knock comes a few minutes into our interview, and I suggest she feel free to eat while we speak. It makes for a relaxed conversation which I can imagine having with an old friend over dinner. She has the ability, even through Zoom, to project a warmth of spirit that would make anyone feel at home and comfortable in her presence.

I know from my research that Ford’s work—as a scholar, as a teacher of environmental studies, as a midwife, as an ethnobotanist, as a writer, and so much more—is marked by a boundless curiosity. “I have lots of interests,” she explains in a recent webinar. “And I’ve tried to pursue them all with enough depth that, the ones that I’m in the most often, I can feel comfortable translating between different disciplines.”

When you start talking with Ford, soon you too find yourself comfortably talking about the interconnections between planetary materials, both animate and inanimate. Her enthusiasm is contagious.

As a self-described lifelong learner, Ford first obtained her undergraduate degree in Biology from Columbia University. Shortly afterward, she moved to California. After a few years and bringing two kids into the world, she attended Antioch University for a Master of Business Administration in Health Administration.

It was then that her overseas travels began. For the nearly thirty years that followed, she traveled the world: Latin America, the Caribbean, South Asia, and Africa. Specific countries included Belize, Bangladesh, Thailand, Cambodia, South Africa, Zambia, Angola, and Mozambique. Her work brought her to remote villages as well as major cities. She trained clinical care workers—she is, among other things, a midwife—and she also taught local people how to set up health systems.

It’s a challenging path few would take on, but Ford wanted her children to experience life outside of the racist systems of oppression in the United States. “It was a very simple calculus,” she says. “I wanted my kids to survive to adulthood. I wanted them to do stupid teenage boy things and not pay for it with their lives. It was not complicated.”

Ford has what she called a “hate/hate relationship with this country” in an address to Goddard College undergraduate students. As she said, “It is the land that holds the blood and toil of my ancestors. The land where I am a citizen by birth and disenfranchised by law and culture. A society that hates me no matter what, even from my subject position of Black and female-bodied and at the bottom rung of society’s ladder.”

She often turns to the wisdom of her Black ancestors …seeing it as an important part of the response to the environmental crisis.

Carrying this history and knowledge, Ford did return to the United States in 2008. That was when she returned to Antioch University, this time to obtain a PhD in Environmental Studies. “I chose Antioch because I needed flexibility. I also wanted autonomy,” she says. “I was allowed to structure my degree to what felt important to me.”

Ford’s studies of Indigenous knowledge from African people who were enslaved in America have unearthed histories that may have otherwise been lost. She also spent time during her dissertation at Antioch diving deeply into the archives at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. Her research into how plants were used as medicine by enslaved African women, Indigenous American women, and women descended from European settlers opened new possibilities for understanding ecological and cultural knowledge. The space where knowledge of plants intersects with reproductive health became a nexus in which Ford could better understand the diasporic lineages she is a part of.

She followed that with an MFA degree in creative nonfiction writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Despite all these studies, when I ask her if, when she looks back, there is anything more she wishes she had done, she answers, laughing, “I hear that as, ‘Would you go back and get another PhD? The answer to that is yes. Oh my God, you have no idea how many times I thought, I’ll just get a master’s in landscape architecture. I’m interested in everything.”

This thirst for knowledge and boundless curiosity runs in her family. She is the third person in her family to hold a doctorate. Her mother held four degrees, two in music and two in education, one of which she completed while pregnant with her daughter. This shaped Ford’s life and her own lifelong commitment to learning.

“I literally have been in the classroom since conception,” Ford says. “I can say without hesitation that it was amazing being raised by a schoolteacher and somebody who felt so passionately about education. It was who she was, not just what she did.”

Today, Ford is a professor in the Environmental Studies Department at the State University of New York at Potsdam. “The greatest thing I’m doing right now,” she says in a recent podcast interview, “is talking to nineteen-year-olds about climate change and the state of the environment in the world right now. And my personal mission is to do that without killing hope.”

She often turns to the wisdom of her Black ancestors for guidance and shares that wisdom in the classroom and with her communities, seeing it as an important part of the response to the environmental crisis.

This all informs her current book project. Describing it, she says, “We experience vastly different and unequal relationships to the resources of our biosphere depending on our race, nationality, and wealth. We have different ideas about the optimal behaviors for a just and sustainable relationship to Earth’s resources depending on our cultural legacies and ancestral wisdom.”

Connecting to her own ancestral wisdom helps guide Ford’s work towards hope, while the current state of the world seems apocalyptic at times. “We’re in transition,” she says. “We’re going towards something, we need to remember that. Otherwise, it’s trauma. Toxic positivity makes us out of balance. Accept that life is hard, and there are good things and bad things.”

It’s difficult to overstate the impact that Ford has had on so many people throughout her life and work. Matthew J. LaVine, her colleague at SUNY, in a letter of recommendation for Ford’s tenure, wrote, “If it came down to Dr. Ford and I, you should not hesitate for a second to renew her contract rather than mine. Dr. Ford’s scholarship, teaching, service, and general importance to the college are simply greater than mine.”

These accolades are lofty, and perhaps it sounds like she is someone difficult to access. That is not the case. With her revolutionary spirit and genuine compassion, Ford is able to distill her ideas down to real action through community building. “I have never met a political quilter like Claudia,” LaVine says. “She brings together communities working on racial justice, gender justice, environmental justice, economic justice, and more—from all different continents, from all different racial, gender, and socioeconomic backgrounds.”

This work is the manifestation of Ford’s vision for the planet, and all that it holds, as one.