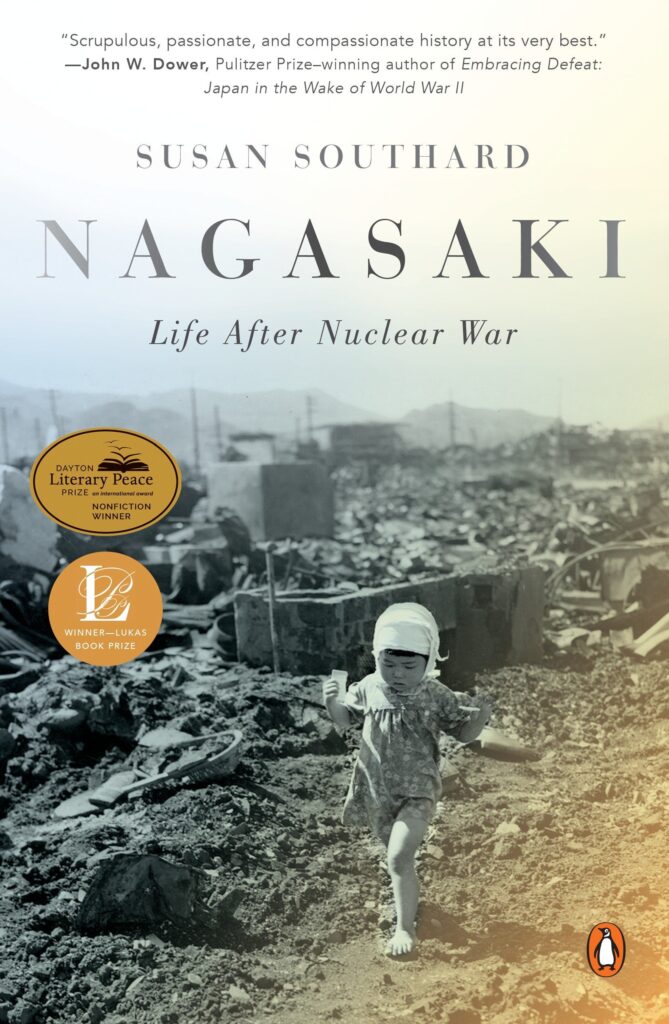

Photo: Pathway through the ruins near the hypocenter on August 10, 1945, between 1 and 2 p.m. To the left, Yamada Eiji is sketching the scene before him. At center, the opening to an air raid shelter is visible, and in the distance are Mitsubishi factory smokestacks. On the hill to the far right stand the ruins of Chinzei Middle School.

Photograph by Yamahata Yōsuke/Courtesy of Yamahata Shōgo

Award-winning author and MFA alumna Susan Southard ’06 remembers feeling “absolutely riveted” the first time she heard survivor Sumiteru Taniguchi describe the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan, and its devastating aftermath.

At a 1986 speech Taniguchi gave in Washington, D.C., Southard listened intently the “dashing” man, then in his mid-50s, described his experiences on the morning of August 9, 1945: One moment he was a 16-year-old boy delivering mail in the mountains on his bicycle, and the next he was sprawled facedown on the roadway with his back literally blown away by the explosion’s searing heat. In that instant, his life as a hibakusha—atomic bomb-affected person—had begun.

“His story was so profound,” says Southard. “For decades, it was just survival after the bomb. The doctors didn’t expect him to live.”

Southard, who speaks fluent Japanese, unexpectedly had an opportunity to work as an interpreter for Taniguchi during his trip, which is when she says “he really allowed me into his life.” She eventually traveled to Nagasaki to meet him and his family, as well as many other survivors, and felt a deep empathy for the stories they courageously and compassionately shared with her.

Southard says their compelling tales became the real seed that ultimately sprouted into her spending 12 years researching and writing Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War.

Published in 2015, Nagasaki intertwines historical facts with the gripping, first-hand narrative accounts of Taniguchi and four other survivors, who were all teenagers at the time of the bombing. The book covers the flashpoint through the 70 years that have passed since that life-altering day.

Widely recognized, Nagasaki earned Southard the 2016 Lukas Book Prize, as well as the 2016 Dayton Literary Peace Prize (alongside two Nobel Peace Prize winners).

When she initially researched the concept of her book, she “became acutely aware and shocked” by the fact that there were no books written in English about the enduring effects of the atomic bombings in Japan. That’s when she decided she had “to get this story out to the world—and to get it right.”

She traveled to Japan in 2003 to begin interviewing survivors and researching local history—the first of five trips and countless hours spent interviewing survivors, experts and historians, walking the grounds, and sifting through huge amounts of archived official documents, photos and survivor testimonials.

From that first trip until the book was published in 2015, she let one question serve as her guiding light: What was it like for survivors, who are in the later stages of their lives, to consider nuclear war as the pivotal event that split their lives in two?

While her intentions were clear, Southard soon realized the enormity of the project she had undertaken, and hired a project historian, Robin LaVoie.

“Robin was absolutely brilliant in helping me identify sources and also helping me to organize the thousands of pages of research,” Southard says. “This book would not exist without her and her participation.” Southard, though already an accomplished writer, also decided that she needed to further hone her writing skills. She enrolled in Antioch University’s MFA program in 2004 to gain further tools to properly tell the “journalistic, million-piece crossword puzzle” that her project had become.

“The MFA developed my skills as a nonfiction writer in so many ways,” she says. “I was a different person when I came out than when I went in.”

LaVoie says Southard’s book is so powerful because she relies on her profound empathy to write the stories of the survivors.

“She really gets into their experiences in a way I haven’t seen other people do before,” LaVoie says. “She just wants to help people get their voice to other people. She listens to them and tries to get the story right.”

Ken Blackburn, a longtime former student who also reviewed drafts of Nagasaki, points out Southard’s passion for helping people share their unique stories, especially the ones that have a societal impact.

“That’s really her life’s work,” he explains. “The purpose of the stories is not just to tell stories, but to change people’s lives.

She is really trying to have an impact on the world through these stories.”

And Southard continues to do just that. Twice, she has shared her research and insights from the book before the United Nations, including being invited to participate in a conference on nuclear disarmament held in November 2017 in Hiroshima, Japan.

“It’s such an honor and a privilege to use my knowledge—to use the suffering and the humanity of survivors—as I speak to the U.N.,” Southard says. “It’s been amazing.”