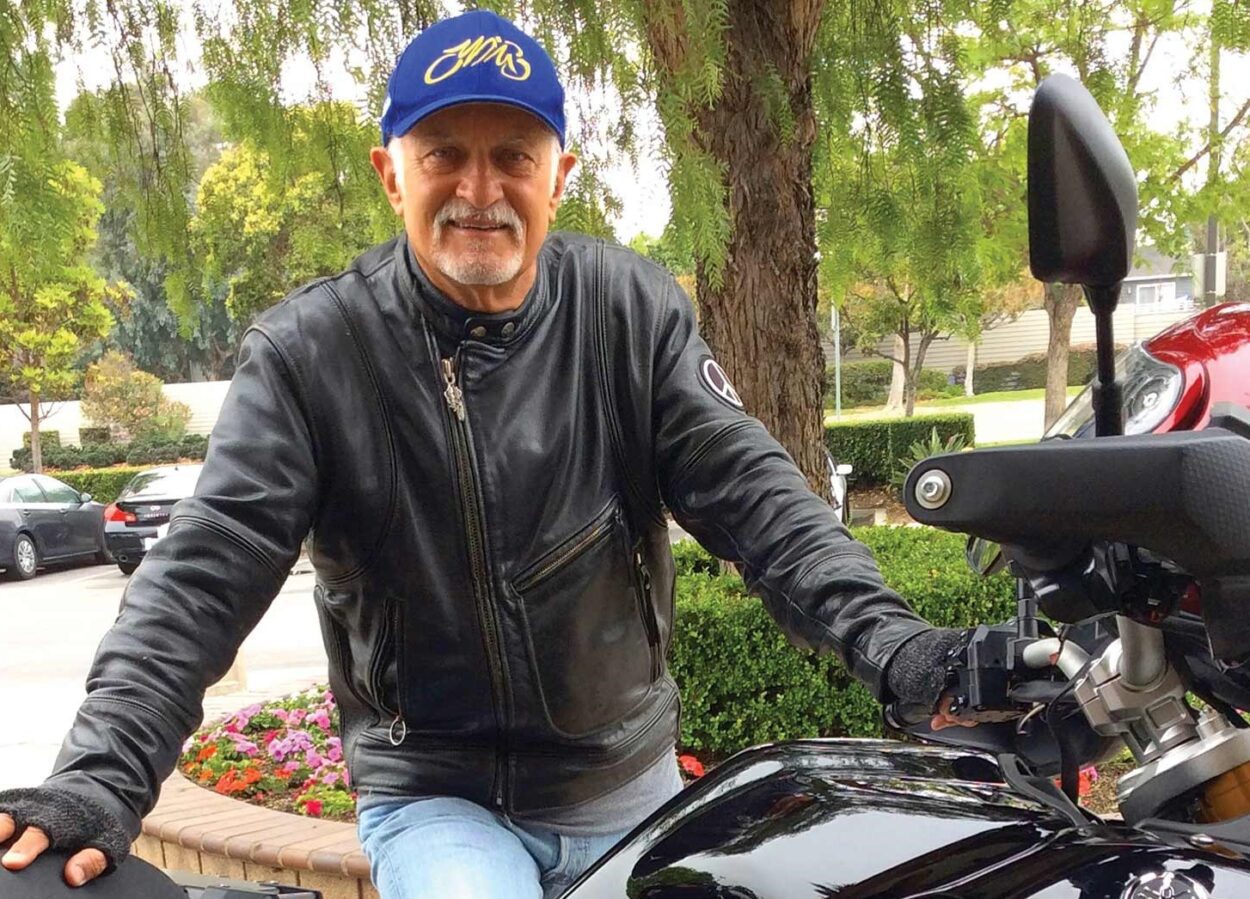

Mark Fargo ’10 (Antioch Santa Barbara, MA in Education, Leadership & Social Justice) rides a motorcycle, but he has no interest in Harley Davidsons or Sturgis. His personal motto is non solum iter: I travel alone. Although he only started riding when he was sixty, Fargo has already traveled all over the country, clocking in over 140,000 miles in just seven years. In that time, he has published three chapbooks documenting his travels in a combination of photographs and haiku. Part Beat poet and part motorcyclist, Fargo is a not a biker. He is a Moto Poet.

“It seems like now I ride through a hundred small towns every trip,” Fargo says. “I ride through the off-the-beaten-path kind of places now—a lot of those two lanes. You know, where they just go on for hours, and I don’t see anybody. For me, there’s nothing that makes me happier.”

Fargo’s story starts long before his days as a Moto Poet.

In another life, he was a teacher. As with most of Fargo’s journeys, the road to his career as an educator was anything but typical. By his own words, he was a late bloomer, landing his first teaching job in his mid-forties.

“I don’t think I would have had the patience of maturity

to do it when I was younger, to be honest,” says, laughing. “I’m glad that I waited to do it.”

As an educator, Fargo was a Jack Kerouac type amongst

his colleagues. He had a soft spot for the students who considered themselves outsiders and nonconformists—ones who didn’t really fit into any clubs. Fargo saw that these kids needed a safe space to express themselves. So he started Beatnik Nation, a literary group and club for the misfits.

“It was the smallest club in the school,” Fargo says. “My colleagues probably thought, ‘Oh, what’s Fargo doing now? He’s got kids reading poetry at lunch in the quad?’”

But for Fargo’s students, Beatnik Nation wasn’t just about hanging out and reading poetry at lunchtime. The group did public performances and readings. Fargo encouraged each student to leave the comfort zone of high school and experience the real world.

After a decade inside the classroom, Fargo started to feel stuck. So at fifty-six, he decided to go back to school to get his master’s degree. At the start of the fall quarter, Fargo visited the Antioch University Santa Barbara campus to see what the program was all about. It turned out to be a perfect match.

“And then they told me, ‘Oh yeah, and your first class starts in two hours,’” he says. “I just kind of embraced the idea that I needed to do this.”

Fargo started working toward his master’s degree that very day. It wasn’t easy, he says, but Fargo has never been one to travel the well-worn road. While he worked on his thesis, Fargo started the BASC Foundation, a scholarship fund for kids who were interested in something that didn’t need a four-year degree.

This was during the “College for All” era, and a scholarship aimed at nontraditional education for students wasn’t a popular idea. Fargo managed all the fundraising on his own, and maintaining the scholarship was an uphill battle.

“But this was the social justice and leadership I’d been learning about,” Fargo says. “We weren’t really giving kids the opportunity to pursue their own careers. We were telling them they have to go to college.”

Fargo raised $30,000 and maintained the BASC scholarship for seven years until his retirement in 2016. By the time of his retirement, Fargo had given twenty years of service, three at the California Youth Authority and seventeen in public schools.

These days, Fargo is on to a new chapter in his life: road trips. When he is on the road, he is strictly a photographer and haiku writer. He isn’t interested in capturing the iconic photo. He doesn’t get off his bike unless he finds something interesting.

“A lot of my friends who travel will ask, where was that shot? Well, it was five minutes outside of the national park. Because no one thinks about that, they go right into the national park,” he says.

For Mark Fargo, life happens on the stretch of road between the photos