It was the summer of 1969 and Frank Galassi ’87 (Los Angeles, MA in Clinical Psychology), a gay college professor from Brooklyn Heights, N.Y., liked to let off some steam and go out dancing at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village a few nights a week.

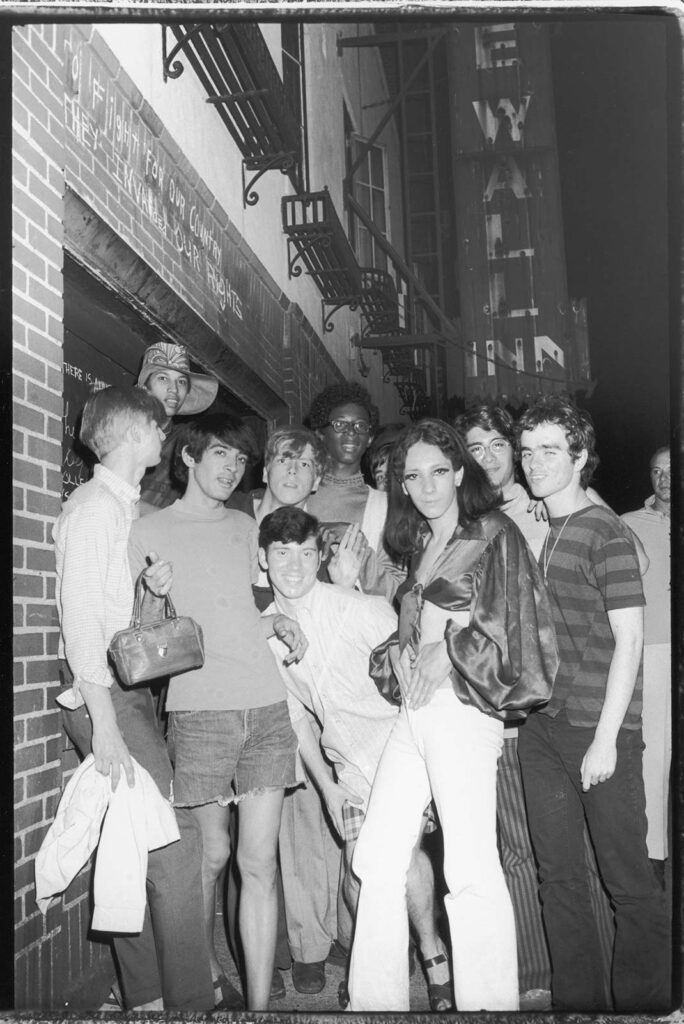

In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, New York City police raided his favorite neighborhood bar, hauling employees and patrons out of the gay nightclub.

The raid sparked a riot among patrons and residents, which led to six days of protests and violent clashes with law enforcement outside the Christopher Street bar, in nearby streets and Christopher Park. The Stonewall Riots served as a catalyst for the gay rights movement in the United States and around the world.

“Looking back we were feeling angry and militant. We wanted something to break open,” Galassi says.

The 81-year-old Galassi now sees the riots and subsequent protests as part of a civil rights continuum, beginning in 1963 with the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

Six years later, after the Sixteenth Street church bombing killed four young girls, Baldwin called for a nationwide campaign of civil disobedience in response.

Galassi clearly remembers Baldwin’s return to the U.S. because it compelled him to take part in the civil rights movement. “Baldwin as a queer black literary figure coming back to the U.S. for political reasons was pivotal in my concept of the continuum of events. To me that was sounding the alarm for the ‘60s and what was to culminate with Stonewall in 1969,” he says.

In 1957, James Baldwin, novelist, playwright, and gay activist, returned from Paris where he had moved to escape persecution to the U.S. He returned that year while civil rights legislation was being debated in Congress and he had been moved by the image of a young girl, Dorothy Counts, braving a mob in an attempt to desegregate schools in Charlotte, N.C. It was suggested he report on what was happening in the South. Baldwin went and interviewed people, also meeting Martin Luther King Jr. in the process.

During those years, Galassi attended a rally at Columbia University in 1968 with a two-fold purpose: to protest the university’s weapons research and a segregated gymnasium that was to be built on-campus. The rally turned into a riot. Other similar student protests were going on around the country. “It was something I’d never experienced before. There was violence all around us, it’s the way it had to be. We were part of a revolution taking place,” he says.

In the 1950s and 60s, very few establishments welcomed gay people, and police raids on gay bars were routine. “Everyone was afraid of undercover police,” he says.

He remembers the night of the Stonewall riots being a Friday. That night, officers from the 64th precinct quickly lost control of the situation. Galassi saw the transgender patrons in drag as the heroes of the riots. “I heard them say, ‘You’re not going to do this to us anymore.’ Some of them were arrested,” Galassi says.

“That was the breakthrough. We saw police weep, they were afraid of us. It was the first time in queer history we got an insight into having power. It was a game-changer.”

The next day he joined the picket line in front of the bar. Over the next several days, the protests outside the Stonewall Inn drew thousands.

“That was the breakthrough.

We saw police weep, they were afraid of us.

It was the first time in queer history we got an insight into having power.

It was a game-changer.”

After the protests, village residents quickly organized into activist groups to concentrate efforts on establishing places for gay men and lesbians to be open about their sexual orientation without fear of being arrested.

On the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall riots Galassi attended the first Gay Pride Parade in New York City and Gay Liberation Conferences in the following years, where he met outspoken gay activists including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera.

Gay academics like himself convened the Gay Academic Union in 1973, where Galassi met notable historians and activists like Martin Duberman, Barbara Giddings and Jonathan Katz.

A new generation of activist organizations emerged in the 1970s, including the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activist Alliance, seeking to end discrimination against gays and lesbians.

Galassi met his husband, Scott, in 1979 during a three-week stay in Los Angeles and moved there about a year later.

“At that time I felt I needed to go back into therapy,” he says. “There were a number of deaths in my family that had impacted me significantly.”

During the Stonewall era, people rebelled against the stigma and the illegal raiding of bars, brutality and the treatment of others as less than. And now look, universities have queer studies. Antioch was in the forefront of that.

Frank Galassi

His therapist asked if he’d ever thought of pursuing the field himself and if he’d heard of Antioch University. He already had his Doctorate in Theater Arts from New York University, but decided to pursue his Master’s in Clinical Psychology. He maintains a small practice today.

“Studying at Antioch was one of the high points of my life,” he says, crediting such faculty as Bob Davis, program founder Harvey Mindess, and program chair Joy Turek as his key mentors. He added his time at Antioch helped him learn the humanistic world of psychology as well as the clinical. “I hadn’t experienced that before,” he says.

“During the Stonewall era, people rebelled against the stigma and the illegal raiding of bars, brutality, and the treatment of others as less than. And now look, universities have queer studies. Antioch was in the forefront of that,” he says.

Today Galassi leads a program for seniors at the Anita May Rosenstein Campus of the Los Angeles LGBT Center, which had a ribbon-cutting this April. It has state-of-the-art classrooms, a culinary school, and a movie theater close-by. A residential building for seniors and young people will be the latest addition. “It’s the first of its kind in global history,” he says.

While so many strides have been made as a result of gay activism since the Stonewall riots, Galassi urges us to be ever-vigilant—especially in today’s volatile social and political climate.

“We’ve got to maintain where we are and go beyond where we are, but we can’t let our guard down,” he said. “We have to maintain strength, commitment and unanimity.”