As the 1960s began, Antioch College was one thing only: a small liberal-arts college with a single campus founded in Yellow Springs, Ohio, in 1852. But some of the faculty had larger ambitions: they wanted to work with graduate students, to offer classes in other locales, and to reach populations beyond middle- and upper-class eighteen-year-olds. Where to begin, though? They saw their first chance in 1964, when a man named Morris Mitchell came knocking.

Mitchell was the director of Vermont’s Putney Graduate School of Education, a small subsidiary of a progressive boarding school, the Putney School. The Putney School had launched the Putney Graduate School of Education in 1950, but by the time Mitchell came to Antioch College, the boarding school administrators were threatening to stop pouring money into the graduate program. So Mitchell was in search of a new partner.

Antioch seemed like it could be the perfect fit: it had its own progressive philosophy, it emphasized work-study much as the Putney School did, and most importantly it had an ambitious faculty with much experience in higher education. The parameters of a deal were worked out, and later that year Antioch took responsibility for the campus and program.

At its launch, the campus was known as Antioch-Putney. It was Antioch’s first graduate program and first “satellite” campus. Its opening ushered in a future that changed Antioch forever, as the University shifted its emphasis from traditional undergraduate education to degree completion and graduate education. It also began the trend of Antioch opening dozens of campuses and centers across North America. Today, the New England campus is one of five that remain part of Antioch University after that period of great expansion.

There are reasons Antioch-Putney survived,” says Heidi Watts, a former instructor there and the author of the monograph, Antioch in New England: The First Eight Years.

“First, there was very good leadership,” she explains. “Second, we had roots in the area because of our links to the Putney School there. That was very helpful. Third, the students were older and more experienced than the typical college students. We were strong enough to start with so that we didn’t have to swing and sway with every turn of the university.”

The Antioch-Putney program began in September 1964—in Yellow Springs. That was where ten students joined the campus’ new director, Roy Fairchild, and met with guest speakers from the Antioch faculty and the local area. In January 1965, the program departed Ohio and shortly thereafter arrived in Putney, Vermont, moving into Glen Maples, a rambling old house atop Mount Putney that had previously hosted the Putney Graduate School.

“It was basically an old home that wasn’t in very good condition,” remembers Claire Wilson, the widow of Norm Wilson, who became the campus’ second director in 1966. “There wasn’t enough space. There was one large seminar room, not a variety of classrooms. Bedrooms were converted into offices for small-group meetings.”

“It was a big, rambling mansion that was always open,” adds Watts, who joined the faculty there in 1968. “The hill was steep, and the drive was not paved, so that was a challenge in winter. Several students lived there and cooked for each other. It was like a commune. I had little kids, so I had my classes in my living room at my house in town. Glen Maples had this large living room where we’d all gather for the weekly seminar and meetings, maybe after a potlach. Some sat in chairs, some on the floor, some lay on the floor.”

It was obvious to everyone how the Antioch co-op model could be adapted to a graduate program in education, because teacher training by its nature requires in-classroom experience. But even with eleven students in early 1965, Antioch-Putney was having trouble finding enough student-teacher slots in Vermont. This shortage of placements was especially acute because most of the students were training to become social science educators.

As he worked to resolve this shortage, Fairchild and his colleague back in Yellow Springs, Ben Thompson, learned from contacts in the Peace Corps that the public schools in Washington, DC, were desperate for teachers. Soon a deal was struck where Antioch-Putney students would teach in D.C. for three-quarters of a certified teacher’s salary. A year later, that program expanded to Baltimore.

“With the advent of paid internships,” Watts writes in her 2000 book, “applications began to flow in, though there were other reasons for this as well. Vietnam was heating up, and the threat of being drafted drove many young men into draft-exempting jobs. Inspired by the call for a new society, other men and women were turning toward work in human-service fields.”

One of those new recruits was David Bury ’69 (Antioch New England, MAT), who had worked for the Peace Corps in the urban slums of Santiago, Chile, between 1964 and 1966. “I’d campaigned for Goldwater in ’64,” Bury says. “But I was also motivated to help people. When you’re living in a Santiago slum, it doesn’t take long to realize that trickle-down economics is a crock of shit, and society needs to provide people born into poverty with more support and more opportunity.”

Bury returned from the Peace Corps to Buffalo, NY, where he started teaching in a public high school and taking education classes at Buffalo State. He soon realized that without well-trained teachers, his high school students weren’t learning as much as they might—and he too wasn’t learning that much in his graduate program. So he went looking for a school that offered more down-to-earth skills and more of a social-justice philosophy. He found it when he noticed an ad for Antioch-Putney in a Peace Corps newsletter.

We came hungry and confused and longing for understanding of why this great war was going on and why our Black fellow citizens were being oppressed. We wanted the truth.

Eva Mondon ’71 (Antioch University, MAT)

“The Peace Corps had shown me that practical learning was best for me,” Bury explains. “I wasn’t a great reader. I learned more from doing things, so the Antioch approach of work-study made a lot of sense. We didn’t want to just talk about what an ideal secondary school would look like, we wanted to put our ideas into action.” He and some other students started looking for a location to establish an alternative school and eventually submitted a proposal to Woolman Hill, a Quaker Conference Center in Deerfield, Massachusetts. The proposal, as Bury tells it, was a success. “Lo and behold, Woolman Hill invited us to come to the 100-acre farm and use the place as the site for the school we were envisioning.” They established the school and ran it for a decade.

Another early Antioch New England student, Eva Mondon ’71 (Antioch University, MAT), had also served in the Peace Corps—in Liberia, in her case. “We came hungry and confused,” she says, “and longing for understanding of why this great war was going on and why our Black fellow citizens were being oppressed. We wanted the truth. Did we find it? Well, I got closer to it, and here I am at 81, still getting closer. I got it not only from the teachers but also from the students and the community. We were engaged with the teachers. You went to their homes. We were like a family, a healthy family. We listened to each other and learned how to listen better.”

Soon after Mondon arrived in Putney in the fall of 1969, some of her Peace Corps friends were joining the Venceremos Brigade, an effort to break the U.S. blockade of Cuba. She told Norm Wilson, who by that point was serving as the center director, that she wanted to go. He not only gave her his blessing but also arranged for it to count as part of her work experience.

“Cuba was on a positive trajectory,” Mondon argues. “But the U.S. felt it was too communist and imposed a blockade. We felt Cuba was devoted to helping its people to survive. Yes, it was terrible that they tried to force people out of being gay or lesbian, but the good outweighed the bad.” Traveling to Cuba during high tensions gave her an inside view of things. “When you’re cutting sugar cane in the middle of a blockade,” she says, “you understand something about survival. And it was a great educational experience. I met people from all over the world, from Africa, from Vietnam, and they all had something to teach me.”

Across so many stories, the gestalt of the times shaped both the form and content of the education at Antioch-Putney. The first ten years of the center spanned the late ’60s and early ’70s, a politically and culturally tumultuous period around the world. The crusades for peace and true democracy, for the civil rights of minorities, women, and gays, and for a healthier environment were woven into everything.

At Antioch-Putney, it wasn’t enough to become a good teacher. The goal was to become a teacher who could make a difference in these issues. “It wasn’t just talk,” says Bury. “When there was an anti-war march eight miles from Putney to Brattleboro, many Antioch students were involved—and at the front of the line was [Center Director] Norm Wilson.”

“Antioch not only embraced those issues but eventually put them into practice,” says Jim Craiglow, who became assistant director of Antioch-Putney in 1975 and eventually director. “If you look at this time that Antioch began to flourish and grow, when the student body exploded in many ways, you can see what motivated the students and faculty. Long before these issues became national movements, Antioch was speaking that language.”

Geography played a role in this. Though Vermont was far from the liberal state it is today, it was tolerant even then. If you taught in the local schools, drank in the local bars, gardened in the yard next door, and bought milk from the local farmer, it was harder to stereotype you as a communist hippie—though some locals still did.

“Antioch New England survived and thrived in a way that says something about the approach of New Englanders to problems,” says Craiglow. “They’ve always been self-reliant, engaged, and involved, attending town meetings. It’s a population that digs in, not a transient group of people. In other areas, maybe people don’t feel as invested in the local community.”

But even as the community could be tight-knit, it also was accepting of difference. Mondon—the student who got credit for protesting the Cuban blockade—had grown up in central Florida knowing that gays were mistreated by wider society, like other minority groups. At the same time, she knew that she was a lesbian. She hoped that if she moved to New England, she could finally come out of the closet. And she did. “People were more about live and let live,” she says.

Inevitably, Antioch-Putney students and faculty wanted to apply belief in participatory democracy not only to society as a whole but also to the institution they were part of. They demanded a say in what courses were taught, how they were taught, who the speakers were, and even how Glen Maples should be decorated. Mostly, the school listened.

Every effort was made to create courses that the students desired. As interest in the environment grew, for example, Ty Minton, a teacher at the Putney School, was recruited to teach an ecology course. Eventually, he traded his teaching for free tuition to earn his master’s degree at Antioch-Putney. One of his projects was drafting a proposal for a new program that would offer master’s degrees in environmental studies. The proposal was taken seriously by Antioch and approved by the administration in Yellow Springs in 1972, along with a master’s degree in psychology. (Both departments continue to thrive, now offering doctorates.)

“Antioch New England was well ahead of other institutions in defining what people needed from their educational experiences,” says Craiglow. “They needed to spend time on counseling, fill a void in environmental activity. People weren’t doing that, but Antioch looked at the world and asked, ‘Who needs to be served? What needs to be learned [beyond] the liberal arts smorgasbord?’”

“We were dissatisfied with the usual, authoritarian approach to education,” Bury says. “Norm was a Quaker, and so was Heidi, so the atmosphere was very Quaker-like. When we had community meetings, the goal was full participation and consensus. There was a sense of affirmation for each of us, because we were included in everything. It wasn’t just about what was wrong with society but what we could do about it.”

As anyone who’s tried it knows, participatory democracy can be aggravating at times. “All major decisions were made as a whole,” Watts says, “and consequently, the meetings went on for hours. One famous meeting spent three hours trying to decide whether we should buy a carpet or not.”

The weekly community seminars could easily become a free-for-all. Mondon remembers the time a man from out of town joined in. Partway through the meeting, he suddenly jumped up to slap his girlfriend in front of everyone. “The other guys tried to grab him, and I jumped on top of the piano,” she recounts. “Norm threw his arms around the guy and just held him. They twisted back and forth and fell on the table, but Norm never let go. Finally, the guy started crying, and I realized I was witnessing something profound. Later I said, ‘Norm, you’re a big guy; you could have bopped him.’ He said, ‘Yeah. It takes more energy to be non-violent than to be violent, but it’s worth it.’ He was an amazing guy, a great role model.”

At one point, the community bumped up against the limits of democracy. As enrollment grew, Glen Maples proved more and more inadequate. “If the program was to grow,” Claire Wilson explains, “it needed more space. It was an old home that wasn’t built for classrooms and offices.” The administration wanted to buy the old Thomas More School in Harrisville, New Hampshire. This would move the operation forty miles east, across a state line and the Connecticut River.

Many among the faculty and the student body, though, had grown attached to Putney. They held one of their classic meetings and ended up voting the proposal down.

Yellow Springs went ahead with its plans anyway, and several students and faculty, including Watts, left the school in protest. “I quit in a huff,” she says. “It’s not a good idea to tell people they can make a decision and then take it away from them.”

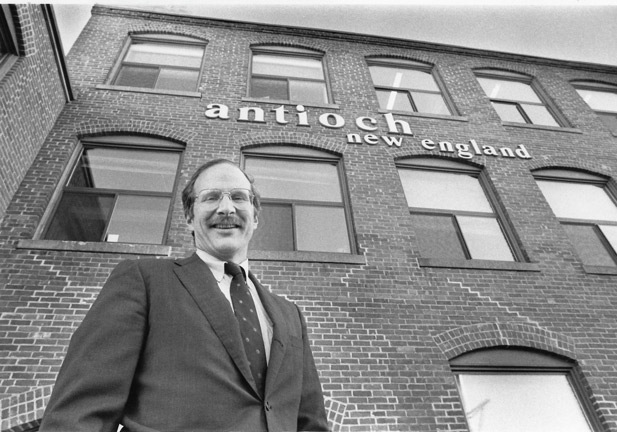

The school moved to Harrisville in 1972, and then it moved again in 1974, to Keene, New Hampshire—a larger city almost directly between Putney and Harrisville. With the move away from Putney, the campus was renamed Antioch New England. It has remained in Keene ever since, though it has twice moved locations within Keene. The university is now planning to move once again, away from its current building, a repurposed furniture factory.

In 1984, twelve years after quitting, Watts moved across the river to New Hampshire and returned to teach once again at Antioch’s New England campus.

In 1972, Norm Wilson died of cancer. He was 46. His widow Claire continues to live in Putney where she works as a potter.

Bury, who now lives in Catskill, New York, founded David Bury & Associates, and for thirty years he used that organization to help nonprofit arts groups raise money.

Craiglow, meanwhile, became president and provost of Antioch New England. He eventually served from 2002-2004 as Interim Chancellor of Antioch University before retiring to Connecticut. He attributes the success of Antioch’s New England campus to its innovation and devotion to serving its community. “We were successful because we were tapping into a new audience,” he explains. “We weren’t dealing with kids coming out of high school, who weren’t used to a lot of experimentation and experiential learning and might need to have their hands held. Plus, there was a shrinking number of graduating high school students in the ’70s. We were working with students who were coming to school for career reasons, not social reasons because they were already on a career ladder.”

Mondon found a welcoming community in Putney and has continued to live there to this day. She has helped establish the town’s first daycare center and first program for survivors of abuse and trauma. For her, the success of Antioch New England depended on putting students on a level footing to collaborate. “We came from very different backgrounds,” she says. “Some had gone to school with Hillary Clinton, and some had gone to school out in the boondocks. There were both moneyed backgrounds and poor backgrounds, and Antioch made that possible by offering work-study funds to those who needed it.”

She continues: “The discussions we had about our education, about the education we saw around us, and about what we wanted to offer as citizens of this country, were so revealing. They helped me find ways to express myself. In some ways, it was as much a spiritual experience as an intellectual experience. There was as much emphasis on the meaning of what you’re doing as on how to do it.”