Between 1964 and 1975, Antioch grew from having one campus in Yellow Springs, Ohio to having more than forty separate campuses, centers, clusters, and circuits spread across the United States and beyond. In the years that followed, a handful spun off and became independent entities, some were absorbed into other institutions, and many eventually closed. Five of the campuses that were opened during that era thrive to this day—New England, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Seattle, and Antioch’s online and distance learning headquarters in Yellow Springs. Together, these five campuses make up today’s Antioch University.

But what about the others? What stories have remained hidden? And how does Antioch’s unique history affect today’s university—and the future? To find out, Antioch Librarian Asa Wilder and University Storyteller Jasper Nighthawk ’19 (Antioch Los Angeles, MFA in Creative Writing) waded through thousands of pages of archival materials, consulted dozens of books, and spent hours talking to some of the people who were there from the start. Most of all, they wanted to understand the legacy of this period of expansion—and to rediscover some of its most interesting stories.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Was the Great Expansion?

- The Wild Growth of Antioch West

- Map of Current and Closed Campuses

- The Center for Understanding Media

- Antioch Columbia and the Pneumatic Campus

- Antioch Law School

- The Communiversity

- Antioch Appalachia

- Juarez-Lincoln University

- George Meany Center for Labor Studies

- The Work of Sustaining

What Was the Great Expansion?

A key distinction of Antioch University among American colleges and universities has been its innovation and openness to experimentation—guided by values of equity and social justice. In its early years, as a liberal arts college with a single campus in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Antioch was known as one of the first schools in the U.S. to admit Black students alongside white students and to admit women to study—and teach—on an equal standing with men.

Later, in the 1920s, under the leadership of Arthur Morgan, Antioch pioneered the “co-op” model of undergraduate study, where students spent significant time, typically one academic quarter out of three, in relevant job placements to supplement on-campus study. Both innovations set the pace for American higher education and blazed a trail that countless other institutions have followed.

But there is no epoch in Antioch’s storied history more marked by experimentation—both overwhelmingly successful and sometimes swiftly unsuccessful—than the period of expansion between 1964 and 1975 when Antioch expanded beyond Yellow Springs to open over forty separate centers and campuses across the United States and beyond.

Each new outpost became a laboratory of experimentation. And the successful initiatives were many. Innovative BA completion programs brought degrees to adults previously excluded from college (Antioch West). Media Studies was formalized as a discipline through the first such degree program in the country (Center for Understanding Media). A low-residency Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing was the first established on the West Coast (Antioch Los Angeles). A Master of Science in Environmental Studies was the first of its kind (Antioch New England). For the first time in the history of legal education, students completed law degrees primarily through law clinics and in-court experience (Antioch Law School). Labor organizers completed BA degrees tailored to their work through a partnership with the AFL-CIO (the George Meany Center). Bi-lingual educators working in migrant communities studied for master’s degrees in the first graduate school tailored to their needs (Lincoln-Juarez University in Texas). And so much more.

It was a time of great innovation, experimentation, and idealism. Each of these forty-plus campuses and centers was a new opportunity to create a more equitable model of higher education advancing access and affordability to underserved populations and communities. How often do established organizations empower so many people to undertake so many wide-ranging and idealistic projects?

The Wild Growth of Antioch West

Antioch’s expansion began in 1964, when the University joined with the Putney Graduate School of Education. (Read “Bringing Antioch to New England” ) But it really got going in 1970, when Antioch used a $20,000 grant to open two new, far-flung centers.

The money was intended for setting up a University Without Walls, which was an exciting term but one not necessarily grounded in specifics. It was based on a British concept of the same name, which involved broadcasting classes over the radio. But the U.S. version of a University Without Walls was being championed by Sam Baskin, the President of the Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities—an institution housed on Antioch’s Yellow Springs campus, and of which Antioch was a founding member. The Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities (which today is a university itself, Union Institute and University) envisioned that Universities Without Walls would bring education to where learners were, without emphasis on grand buildings or big, handsome libraries. Instead, they would take existing resources and apply them to pressing community needs.

In service of this vision, they applied for and received a grant of $400,000 from the Ford Foundation and the U.S. Office of Education. This money was split between the various universities in the union, and Antioch received $20,000. That was when Jim Dixon, then President of Antioch, and Morris T. Keeton, who at the time was Antioch’s Vice President of Academic Affairs (Keeton later founded the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning on Antioch’s campus), decided to use the money to open new campuses—or “centers.”

At the start, each new campus was envisioned as having two separate parts. One part was the “Antioch Center,” which was a home base for Antioch students who wanted to study somewhere other than Antioch’s main Yellow Springs campus. The other part was the “University Without Walls,” in which anyone who lived near the new Center could enroll.

But where would the first Antioch Centers / Universities Without Walls be opened? Dixon and Keeton decided to split the money in half. They sent $10,000 to Philadelphia, where they partnered with a community organization that wanted to help teachers get degrees. The other $10,000 went to Joseph P. McFarland, a psychology professor, and Jim Jordan, a professor in the Art Department, to start a center in San Francisco. This initial seed money would end up growing into three of today’s campuses.

McFarland and Jordan had for years been lobbying to go to San Francisco and teach psychology and art students there. Now they had their opportunity. However, they knew they needed someone on-site, and they still had faculty responsibilities in Yellow Springs. They offered the opportunity to one of McFarland’s advisees, who was engaged in an independent learning program at the time. That was Lance Dublin ’73 (Antioch College, BA), who finished the last two years of his Antioch College degree while also setting up a new wing of the University on the West Coast.

“I said, ʻSure, Joe. I’ll leave the miserable winter in New Jersey’—where I was interning with the Commissioner of Education—ʻto go to San Francisco.’ Who wouldn’t?” recounts Dublin today. “So that began my career in higher education.”

After an initial visit to San Francisco that resulted in an article in the San Francisco Chronicle, they received an invitation to move rent-free into a warehouse owned by a local business family. By the end of the summer, the Center was launched, taking space in the warehouse for this first campus. McFarland moved to San Francisco to be the Director, and Dublin served as the learning coordinator even as he was finishing his own undergraduate studies. “It was my duty to find job placements for other Antioch students, so they could learn through Antioch’s co-op model, and to locate learning resources for the University Without Walls program students, who most typically had full-time jobs.”

At the same time, there was conflict around the bifurcated nature of the campus. The students who had matriculated at Antioch College were technically studying at Antioch’s San Francisco Center, while the people who already lived in San Francisco were studying at the University Without Walls. Except that the second school—operating through the Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities—wasn’t yet accredited. At the same time, the faculty back in Yellow Springs was very concerned about giving degrees to non-Antioch students. Eventually, Keeton convinced the academic council to let the satellite campuses use Antioch’s accreditation for all students. So the bifurcation ended.

This was a good thing, because there was a great demand for an Antioch education in San Francisco at that time. “It was a ripe area,” says Dublin. “You had two historic academic institutions, Stanford and Berkeley, but they weren’t interested in changing. And you had the huge social change movement in California, people trying to live lives aligned with their values and committed to social justice. They all were well-suited to Antioch’s mission and the University Without Walls model for higher education.”

The campus was so successful that other groups soon learned about it and began asking if they could become part of this new campus. Often, the answer was yes. Antioch West, as this wing of Antioch, came to be known, partnered with organizations like the Primal Institute in LA and the Cold Mountain Institute on Vancouver Island, which both wanted to offer for-credit psychology classes. Eventually, after many requests from community groups, it was decided to open a full-blown campus in Los Angeles. Dublin hired the new LA campus’ first director, Al Erdynast, right out of a doctoral program at Harvard Business School. (Read our story about Erdynast’s fifty years at the Los Angeles campus)

Dublin remembers the madness of trying to run one center while setting up another one four hundred miles away. “At that time, you could fly from San Francisco to LA in 58 minutes,” he says. “So: get up in the morning, fly to LA, do a bunch of work in LA, fly back to San Francisco for meetings in the afternoon, and then fly back to LA that night for student orientation and student meetings.” McFarland was running the academic side of Antioch West, while Dublin, who was still a student, did the administrative legwork.

With the success of the Los Angeles center, they next opened a center in Seattle. At the start, the Seattle campus consisted solely of advertisements in local newspapers—and a telephone set up in Dublin’s sister-in-law’s basement. Antioch paid her to answer the phone and start recruiting students. From there, they built the campus.

Antioch West opened campuses in Honolulu and Corpus Christi. Even the North Slope Indian Council memorably worked with McFarland and Dublin to open the first university campus in the U.S. north of the arctic circle, Antioch West: North Slope in Barrow, Alaska.

It was a heady time, and for Dublin, it launched him as a professional. His many responsibilities at Antioch West were wildly beyond what most people do during their college years. He stayed on as Administrative Dean after graduating from the College, and by age 25, he even served for a few months as Acting Provost of Antioch West, most likely the youngest provost in the country at the time. But by that time the period of expansion was over. Antioch’s new President, William Birenbaum, did not think it was in the interest of the University to have such a young person, with only a bachelor’s degree, in a position where he was responsible for bachelor’s and master’s degree programs and hundreds of core and adjunct faculty. Dublin left Antioch and went on to a successful career in corporate learning and development and management consulting.

Antioch West continued. Some centers closed, but three have remained open to this day and are key campuses of the current University: Los Angeles, Seattle, and Santa Barbara.

Map of Current and Closed Campuses

This map shows all known Antioch campus locations, both past and present.

The Center for Understanding Media

Antioch’s expansion soon reached New York City, where a partnership with Harlem Hospital created one of the first Physician’s Assistant programs in the country. Teachers, Inc. joined with Antioch to provide innovative teacher training. But perhaps the most notable of Antioch’s partnerships there was with the Center for Understanding Media, a group founded in Greenwich Village in 1969 by John M. Culkin, a renowned media theorist and Jesuit priest who is now widely considered the inventor of Media Literacy Education. At that time, though, he was just getting established. Culkin was a longtime collaborator and colleague of Marshall McLuhan, the author of Understanding Media, a profoundly influential and bestselling book that became the canonical text of this new field of Media Studies, with Culkin as its primary interpreter and promoter. At the Center for Understanding Media, Culkin established a community of academics and media practitioners to advance the field.

In its first years, the Center functioned independently, as a kind of think tank and education hub, holding workshops and lectures on the importance of understanding new media like video and telecommunications. In 1972, the Center opened its summer program to Antioch graduate students, who, due to Antioch’s bold, expansive approach to higher learning, could now earn credits toward their degrees. Then, in the fall of 1973, the Center and Antioch partnered to launch a first-of-its-kind MA program in Media Studies. With more than seventy-five students enrolled as degree candidates, the Center was laying the groundwork for the thriving field of study we see today.

According to Deirdre Boyle, a renowned professor of Media Studies and member of the first graduating class from the Center, “The development out of the workshop model into a graduate program evolved when Antioch agreed to sort of embrace this master’s program as one of its satellites.”

Boyle described her time as a master’s student at the Center in a 2012 oral history interview. “We did some rather interesting research, at least at the time. And John [Culkin], who was a magnetic, charismatic figure and sort of galvanized people and drew them into the circle here, brought in extraordinary teachers and guest lecturers. Susan Sontag was a lecturer while she was writing her historic series of essays for the New York Review of Books, on photography that would change the way everybody thought and wrote critically about photography. And while she was doing that, she was a guest in class.” With lectures from figures like Sontag and McLuhan, the program doubled in size in its second full year, offering twenty-five courses in the 1975 academic year. During the Antioch years, the Center’s faculty included Kit Laybourne, who would go on to produce popular television shows for Nickelodeon and MTV, and Pete Fornatale, a DJ and author known as “the pioneer of F.M. Rock.”

Due to complications with New York’s accreditation system, the Center’s affiliation with Antioch ended in 1975. But in many ways, this was only the start. After Antioch, the Center’s new MA program was integrated into the New School and eventually became that university’s School of Media Studies. Today, the School of Media Studies has an enrollment of about 275 graduate students and employs 30 full-time faculty, including Boyle.

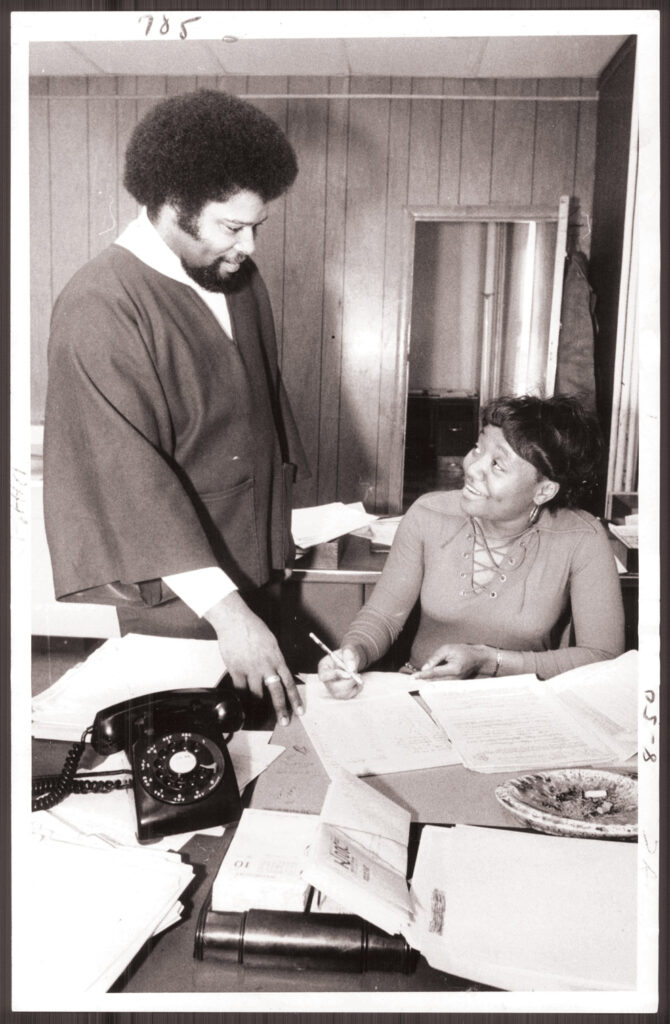

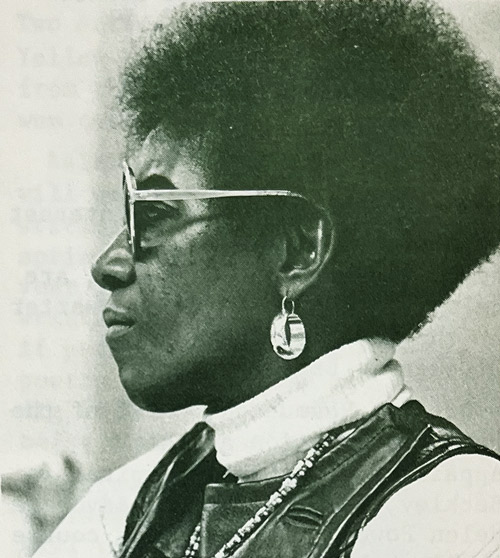

In this archival photo, Charles W. Simmons ’70 and Betty Gladney ’74 complete work at Antioch’s Homestead-Montebello Center in East Baltimore. Simmons co-founded this campus on a shoestring after himself graduating from Antioch Baltimore. As he recounted in an oral history for the 2018 Antioch Alumni Magazine, “In the early days we had to rely on an all-volunteer faculty and staff.” In 1980 the Center spun off from Antioch to become Sojourner-Douglass College, with Simmons as President.

Antioch Columbia and the Pneumatic Campus

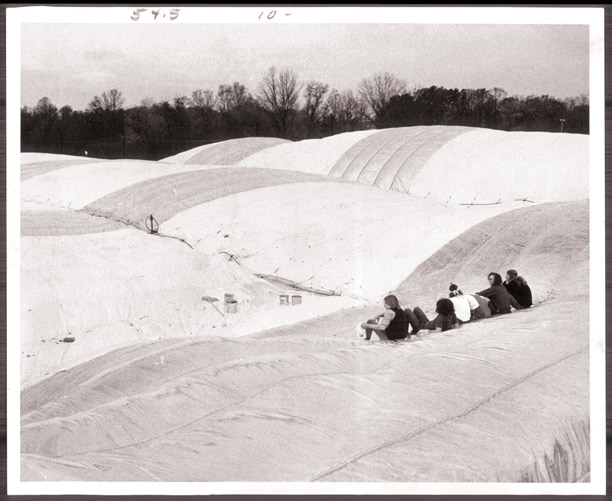

Other experimental campuses were even more audacious. On November 1, 1972, a 32,000 square-foot pneumatic dome was inflated at Antioch’s Columbia-Maryland campus by a five-horsepower electric fan. By May of 1973, the campuses offices and classrooms had all been situated inside the bubble to test the practicality of air-supported structures. Costing roughly $178,000, the hands-on learning project was federally funded, with students receiving credit for calling in manufacturer orders, negotiating building contracts, and asking for material donations from corporations. The process-oriented curriculum meant students learned about design as well as the real-world skills needed to complete such a large project. In the final narrative report on the project, James Brann says, “The concept of the bubble developed in a strange manner, in a pattern of events that could only happen in a place like Antioch.” It all started when 21-year-old Blair Hamilton convinced a rubber company to give him a ton of scraps—and began experimenting with what he could make. In a fascinating series of steps, Hamilton secured a grant to build the bubble and garnered a staff appointment while completing his undergraduate degree.

Overall, the building of the bubble meant that two projects were being taken on by faculty and students—the physical construction and the construction of a new kind of curriculum. It worked gloriously for students who had been to college before and were entering with plans of their own. Other students felt adrift and left out when professional designers and consultants stepped into leadership positions. The structure was flattened in November 1973 by an early Nor’easter.

Antioch Law School

Established in 1972, the Antioch School of Law envisioned a new way to train lawyers. Rather than solely reading through old appellate cases and sitting through classes founded on the traditional Socratic method of teaching, Jean Camper Cahn and Edgar S. Cahn created an institution where students learned from teacher-lawyers by helping them represent actual clients in real courtrooms. They were radical in their approach to instilling a sense of the needs of disenfranchised communities. The first years saw students living for weeks with families who were impoverished in Washington D.C. to better understand their lives. In a time when women made up ten percent of the student population in most law schools, Antioch School of Law had equal gender representation in 1975. They welcomed students with less traditional educational backgrounds, knowing experience, and real-world knowledge to create stronger institutions. That same year, 35 percent of students were Black or other people of color. The mission was not just to create a law school but a class of public interest lawyers dedicated to legal access and social justice.

The law school was accredited by the American Bar Association, but that accreditation was fraught since its inception over issues about the size of its law library and faculty pay. Those pressures eventually led to its closing in 1986. It was almost immediately re-established by the DC City Council as the District of Columbia School of Law and is now the University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law. The school retained Antioch’s mission, curriculum, clinical programs, faculty, and personnel. And many of its innovative approaches to teaching law have become deeply embedded across our education systems. The school developed the framework of clinical legal education, which provided pro-bono legal services to people who couldn’t otherwise afford counsel. The model is now recognized by the American Bar Association as essential to a complete legal education.

Antioch v. Deep Throat

For the first class Sherwood Guernsey ’75 took at Antioch Law School, he was told to sit in on the highly public obscenity trial around the pornography film Deep Throat. He loved it—and loved the education he got there. “All the professors were actively practicing attorneys,” he explained in a profile in the 2021 Antioch Alumni Magazine. “They would have us analyze and go into court on actual cases they were working. That made all the difference.”

The Communiversity

Another experiment from this period was a North Minneapolis campus called the Communiversity. It was founded by the activist and educator Gwyn Jones-Davis, who had previously co-founded a community center called The Way. (The Way’s house band was led by a teenage guitarist named Prince Rogers Nelson). Now, as she started this Antioch-affiliated campus, she focused her programs on incarcerated and recently-incarcerated people. Little documentation remains about this forward-looking campus, but a tantalizing trace of Jones-Davis’s sense of mission comes through in a recording of testimony she gave at a public hearing on juvenile incarceration. This recording aired on February 14, 1975, on Minnesota Public Radio, foreshadowing by 35 years some of the arguments that Michelle Alexander would make in The New Jim Crow.

“When you begin to talk about treatment, then you determine somebody to be sick. I happen not to think they’re sick. I happen to think that it’s a whole different way of looking at the world… I think it was created coming out of the push of professionals and the ‘mercy syndrome’ that says, ‘let’s help the poor people,’ that broke up the neighborhoods, so people don’t have things to hold onto. And when you try to create artificial things to hold onto, it just doesn’t make any sense, so you get to the point where you really don’t care about anything. I’ve yet to find a young person—and this is out of my whole experience coming from 1962 when I worked on the west side of St. Paul with Native Americans and Chicanos and poor European-Americans—I’ve yet to find one of these children, however bad they may be, whose parents did not care about them nor where they were ever too busy to take care of what the kid needed, and, second, therefore, the kid didn’t give the same respect back to the parent. When you deal with what we’ve defined as what we call ‘the good kids,’ I think that’s where you hear of people saying, ‘My parents don’t understand me. I don’t understand my parents.’ Where is the sickness? It depends on the criteria that you’re using to measure them against.”

The Communiversity closed in 1976 when Jones-Davis received a prestigious American Council on Education Fellowship.

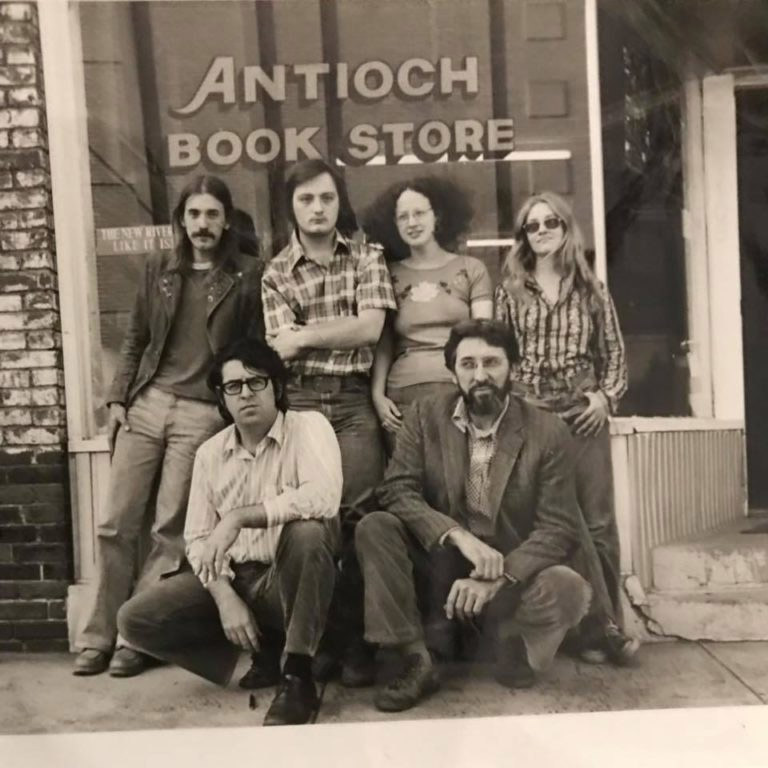

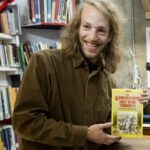

Laura Speight-Reddick ’80 browses books at the campus bookstore at Antioch Philadelphia. “Antioch changed society,” said Reddick in our oral history of this campus in the 2021 Antioch Alumni Magazine. “If you look at Antiochians in Philadelphia, they are doctors, lawyers, and educators—and, whatever they’re doing, they’re trying to make society better. That’s because we were in a college for social change.”

Antioch Appalachia

Antioch seemed to make a point of allying with people who were trying to elevate their local communities. In the early 1970s, Antioch Appalachia and its founder Bob Snyder became central figures in what became known as the “Appalachian Renaissance.” In an interview with the Urban Appalachian Community Coalition, former Antioch Appalachia student and founding member of the Soupbean Poets, Pauletta Hansel explained, “The Appalachian Renaissance was connected both in time and spirit to the Black Arts Movement, the writers of Second-Wave Feminism, the Native American Renaissance, and other identity-based literary movements of the ’60s and ’70s.” For those associated with it, the Appalachian Renaissance was a chance to reclaim “hillbilly” identity, and to work to create a positive regional identity and pride.

Antioch Appalachia—originally known within Antioch as the Southern Appalachian Circuit—provided a place for this innovative work from its headquarters in Huntington and then Beckley, West Virginia. Its coursework included interdisciplinary social science work that centered on its BA completion program for adult learners. It was also home to a literary journal, What’s a Nice Hillbilly Like You…? And Snyder, together with Antioch students like Hansel and another faculty member, P. J. Laska, formed the “Soupbean Poets,” a prolific poetry collective with an activist bent.

In addition to Snyder, the faculty included poet, educator, historian, trade union organizer, and civil-rights activist Don West, who founded both the Highlander Folk School in New Market, Tennessee, and the Appalachian South Folklife Center in Pipestem, West Virginia, where he lived with his wife, the painter and educator Connie West. The Folklife Center was focused on “the restoration of self-respect and human dignity lost as a consequence of the region’s colonial relationship with industrial America” and served as a natural partner for Antioch Appalachia. Throughout the early 1970s, the Wests hosted Antioch programs and events on their farm in Pipestem, and in 1975 Antioch students even undertook a project to equip the farm with wind power.

The Antioch Appalachia campus closed in the late ’70s, but West, Snyder, and other members of the Antioch community remained central figures in the region. Snyder went on to help found the Urban Appalachian Community Coalition and the Southern Appalachian Writers Cooperative while continuing to write and publish poetry. West’s Folklife Center remains in operation to this day. The spirit of Antioch Appalachia is perhaps best summed up by the former Antioch student and “Soupbean Poet” Pauletta Hansel, who recalled in a 2012 essay: “I chose Antioch Appalachia because it was a college that would have me: 16, bright, diploma-less, and determined to shake the coal dust from my bell-bottom jeans and live the literary life.” Ultimately, Antioch Appalachia played an early, key role in fulfilling the mission given to it by the University: helping adults complete their bachelor’s while “stressing the region as a crucial image for understanding the world.”

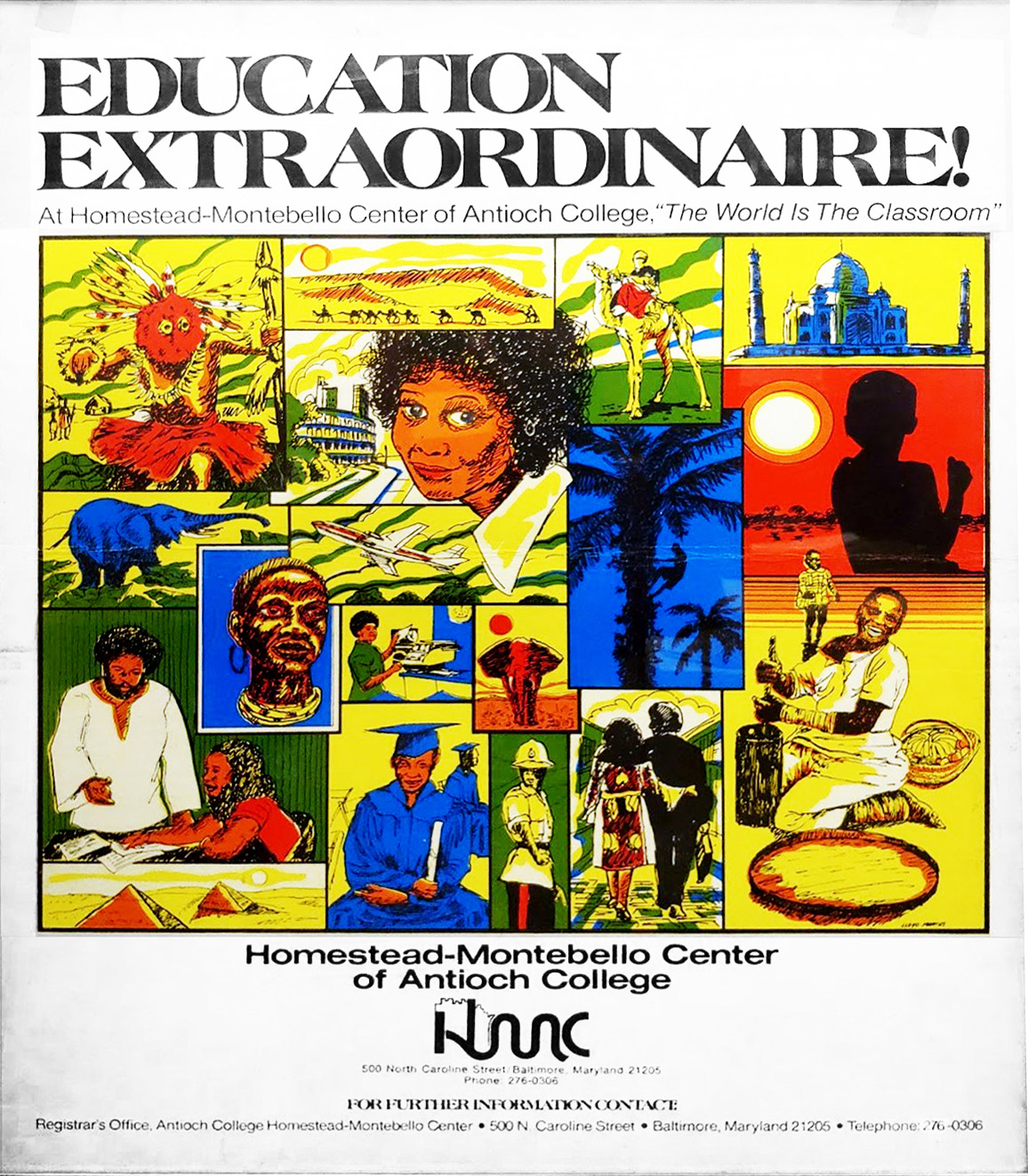

Archival poster from the Homestead-Montebello Center in Baltimore.

Juarez-Lincoln University

A major theme of the expanding Antioch Network was bringing education to people who were disenfranchised from traditional college—and to change what education looked like to make it relevant and rooted in the experience of people who weren’t white, middle-class Midwesterners. To achieve these goals, they often teamed up with local activists already doing this work. That’s what brought Antioch to Texas.

The Juarez-Lincoln Center emerged out of the burgeoning Chicano Movement and the 1969 conference of the Mexican American Youth Organization in Mission, Texas. It was among the first institutions of higher education dedicated to bilingual and bicultural instruction with a curriculum based in Chicana/o history and culture. Founded by Leonard Mestas of Denver and André Guerrero, the Juarez-Lincoln Center initially operated out of a small office in Fort Worth, Texas. Then, in 1972, Mestas and Guerrero opened a dedicated campus in Austin, Texas, and formed a partnership with the Antioch Graduate School of Education to offer master’s degrees in Education.

Over the next three years, the Juarez-Lincoln Center would launch a bachelor’s program in liberal studies through Antioch College, open extension campuses in Denver, San Antonio, Mission, and Corpus Christi, and become known as Juarez-Lincoln University. The bachelor’s program at Juarez-Lincoln University employed an interdisciplinary structure, organized around the five themes of communication, environment, social progress, humanities, and professions, designed to “prepare the student to serve as a social change agent for the Chicano community.” They also utilized a service-learning model harkening back to the Antioch co-op model, offering course credit for work done in the community.

The campus also served as a central information hub and meeting place for activists, educators, farm workers, and other people in the Chicano community. It housed the National Farmworkers Information Clearinghouse, a resource center for migrant farmworkers and migrant programs with national distribution. Antioch University and Juarez-Lincoln University parted ways in 1979, but the Juárez-Lincoln building remained a central meeting place for East Austin activists, hosting many groups, including the League of United Chicano Artists and Mujeres Artistas del Suroeste.

LOOKING BACK AS A LIBRARIAN

“When I started my position as a librarian in early 2020, I didn’t know much about the history of Antioch University,” writes co-author Asa Wilder in an online-only extra about finding himself at Antioch. “But over the last two-and-a-half years, as I have been welcomed into our university’s community, I have discovered an incredible maze of stories, experiences, resonances, and connections, both personal and professional, that tie me to Antioch. It seems like the deeper I dig, the more concomitance I encounter. And never was that more true than when I visited Antioch University’s archives last April…”

George Meany Center for Labor Studies

A devotion to training workers and underprivileged people eventually extended to teaching those trying to organize those workers. Initially established in 1969 as a training center for the AFL-CIO, the largest federation of unions in the U.S., the George Meany Center for Labor Studies began partnering with Antioch in 1971. Later that year, the Center moved from downtown Washington, DC to a dedicated home in a former seminary in the suburb of Silver Springs, Maryland. Like many of the programs and schools that emerged during this period, the George Meany Center was designed to meet the educational needs of those not served by traditional educational formats. In this case, that meant union officers, staff, and other labor leaders who—due to “heavy travel schedules and the pressure to appear at irregularly-scheduled meetings—were not able to pursue their entire college program at conventional institutions.” Without any age or previous educational requirements, priority for admission was given to full-time union staff and elected officials.

Under Executive Director Fred K. Hoehler, Jr. the George Meany Center hosted residencies and workshops to train organizers. It also offered one of the nation’s few bachelor’s programs in Labor Studies. The faculty of labor leaders and academics taught courses like Collective Bargaining, Labor Movement History, Economics, Protest Literature, Political Science, and Fine Arts. They even lead workshops like “The Great Labor Song Exchange,” a three-day residency “designed to preserve and promote labor’s inspiring musical tradition” that culminated in a large public performance in the campus theater.

The partnership between Antioch University and The George Meany Center lasted for almost 30 years. In 1997, the Center received degree-granting authority from the State of Maryland Higher Education Commission, and under the newly-appointed dean, Susan J. Schurman, the George Meany Center spun off and became the independent National Labor College. Unfortunately, over the next decade-and-a-half, it faced declining numbers in union membership, increased expenses for upkeep, and anti-union backlash from conservative politicians. The National Labor College struggled to maintain enrollment numbers, especially after relocating to the newly built Lane Kirkland Center campus in 2006. The National Labor College continued granting degrees until its closing due to financial difficulties in late 2013 when it sold the campus. Now those buildings house the Tommy Douglas Conference Center.

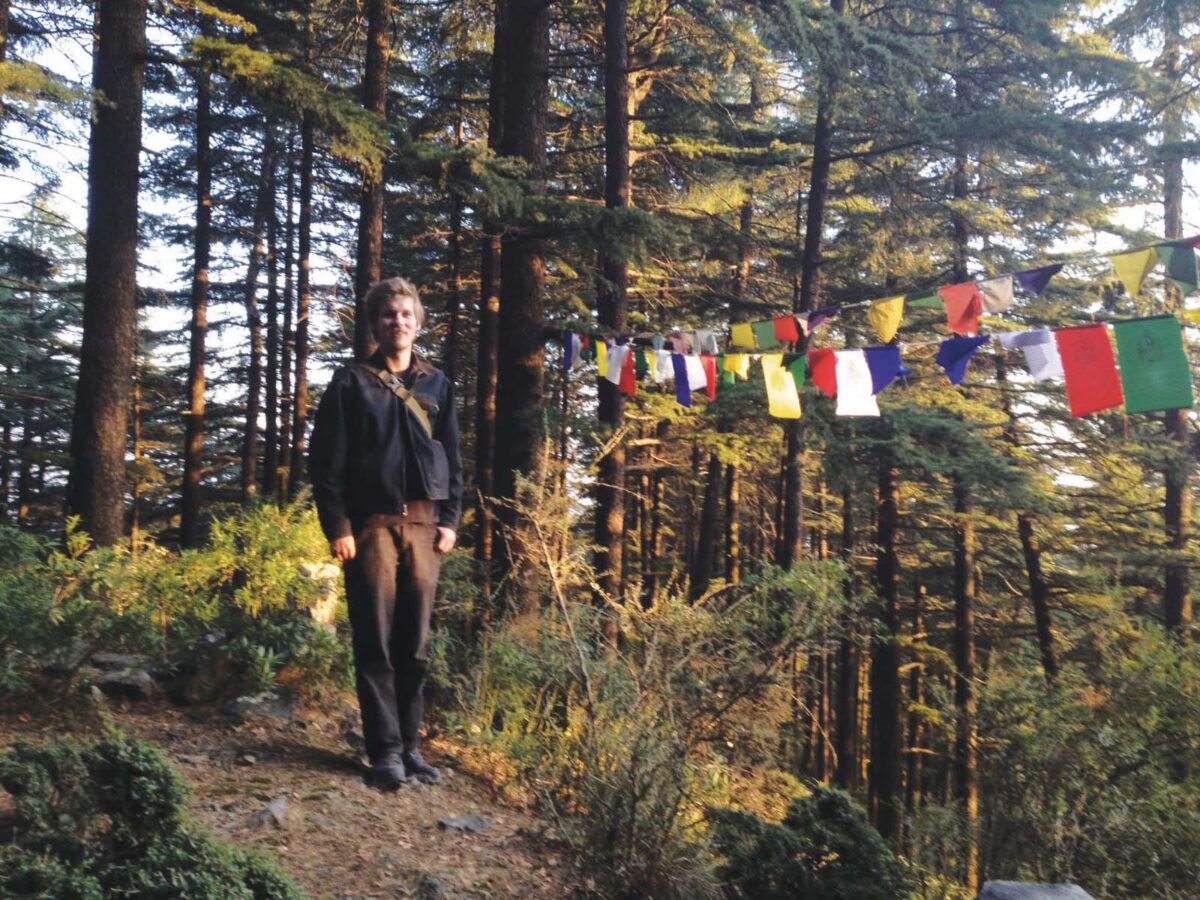

ANTIOCH UNDER THE BODHI TREE

In an online-only extra, co-author Jasper Nighthawk remembers how his first encounter with Antioch University came when he showed up, unenrolled, at Antioch Education Abroad’s Buddhist Studies program in Bodh Gaya, India. His girlfriend was studying abroad there and, he writes, “We did get to see the Dalai Llama, who was leading a multi-day initiation, ordaining the gathered nomads into an esoteric, lay tantric order. (We left after several hours, when a friend told us that if we stayed we would have to commit ourselves to these practices for the rest of our lives.) Even now, a decade later, I can remember every day of that time so vividly.”

The Work of Sustaining

This remarkable period of expansion did finally come to an end—an end that can best be traced back to the resignation of Jim Dixon as President of Antioch. While Antioch’s trustees had for the most part stood behind their president and his efforts to make higher education more accessible, they had faced a great deal of criticism from faculty at the original College campus, which after the expansion no longer formed the majority of the University. There had been a protracted and divisive student strike over financial aid in 1973. And there emerged a persistent narrative that the other parts of the network were a financial drag on the original campus. (Most accounts say quite the opposite, that funds consistently flowed into the College from the other campuses.) Nonetheless, there was a concerted push for regime change.

In March 1975, Jim Dixon finally tendered his resignation, effective June 1977 or “at such a time as a successor is chosen.” The Chronicle of Higher Education saw this as a win for Dixon, who the trustees chose not to fire after two days of closed-session meetings in a Manhattan hotel. But the writing was on the wall that things would change, and within months Dixon was gone, and Morris Keeton stepped in as Acting President.

It was right at this juncture that the law firm Martin, Browne, Hall, and Harper, PLL—the Springfield firm that had represented Antioch since 1921—assigned a young lawyer named Dave Weaver to assume primary responsibility for Antioch’s legal work. The lawyer who was handing it over, Oscar T. Martin, III, told Weaver, “Antioch has been my most interesting client over my career, and as long as you are involved with it, it will be your most interesting client as well.” That proved to be immediately true. The first trustee’s meeting he attended was the one where Dixon’s departure was negotiated. As Weaver puts it, “While I didn’t attend Antioch, I always say that I got a great Antioch education.”

Weaver had front-row seats to see the last months of Dixon’s tenure, who he describes as having a good personality for founding things but not necessarily seeing them through. “He was a smart but not very well-disciplined fellow,” says Weaver, “and he just kind of let things run their course. He liked new ideas, and he liked the notion of letting people do what they really felt energized and able to do.” But most of what Weaver got to see over the next four decades was the way that Dixon’s successors and their teams have done justice to the many campuses opened during the expansion—while keeping Antioch University sustainable to the present day.

In the years after expansion, many of the campuses ended up joining—or becoming—other universities. The Center for Understanding Media became the #1-ranked Media Studies program at the New School in New York. The Institute for Open Education became Cambridge College. The Homestead-Montebello Center in Baltimore became Sojourner-Douglass College. The Physician’s Assistant Program at Harlem Hospital became part of the New School and today is part of the CUNY School of Medicine.

When Alan Guskin became President of Antioch University in 1987, he told the board that he could save the College or he could save the Law School, but he couldn’t save both. The innovative Antioch Law School ended up closing, though later it was reformed as the David A. Clarke Law School of the University of the District of Columbia.

Other campuses were shuttered. “Most of the closures had teach-out plans,” explains Weaver, “so that they didn’t kiss off the enrolled students. They stopped enrolling new students.” But for the students, faculty, and alums who had poured so much into making a campus work there was still grief in seeing it close.

Throughout it all, Antioch University has kept its doors open and, through the surviving programs, found a much larger footprint across the country than it had before the period of expansion.

Weaver himself continued as University Counsel for 32 years, worked for six different Chancellors, flew across the country to over 125 board meetings, and oversaw the closure of many of the University’s campuses and centers. His last meeting was in June 2007, at which time the Board of Governors voted to suspend the operations of Antioch College for reasons of severe enrollment decline and financial exigency. At that point, he asked his younger partner and protege, Bill Groves, to assume the reins as lead University Counsel. Groves led the negotiations culminating in the sale of the College campus to a new, alumni-led corporation in 2009. He became the first in-house General Counsel in Antioch history in 2010 and became Chancellor of Antioch in 2016.

Today’s Antioch University, which Weaver played a key role in sustaining, is composed of five campuses and online offerings that reach worldwide. These campuses are much more tightly integrated with each other than they were in the early days of what came to be known as the Antioch Network. But they have deep in their history and DNA the powerful memory of this time. Each campus open today is a descendant of one established during the period that was striving to expand the possibilities of higher education.

“With the hindsight of looking back in time, it wasn’t a failure,” says Weaver. “We’ve got some really important and vital campuses around the country that are doing a lot of great work reflecting the value and the mission of Antioch University as it has existed for 170 years. I call that success.”

Correction: A previous version of this article said that Antioch Santa Barbara was launched by a graduate of Antioch Los Angeles. That is not the case. It was Lois Phillips who Lance Dublin hired and empowered to locate a facility and hire a faculty, leading to the launch of BA and MA programs within three months. Please read our oral history of the founding of that campus to learn more.

Jasper Nighthawk

Jasper Nighthawk ’19 (Antioch Los Angeles, MFA) is Antioch University’s Manager of Communications. He hosts the award-winning Seed Field Podcast and co-edits Common Thread and the Antioch Alumni Magazine. In his free time, Jasper is a writer and publishes an email newsletter called Lightplay. He lives in Los Angeles and on the Mendocino Coast with his partner, child, and cat.

Asa Wilder

Asa is the Reference and Instruction Librarian supporting the Undergraduate Studies and MFA in Creative Writing programs at Antioch University. He received his MLIS with a concentration in Archival Studies from UCLA in 2019 and began working at Antioch in early 2020. Before moving to Los Angeles to complete his graduate work in Information Studies, he worked as a Reference Librarian for his hometown Kansas City Public Library, a paralegal in Baltimore, Maryland, and a barista in many now-defunct coffee shops.