For decades, José Ramos-Horta labored for the freedom of his country. His journey led to the UN, to Antioch, and even to the Nobel Peace Prize. Nothing was as good as going home.

While so many people immigrate to the United States that the “immigrant story” is both national myth and political bugbear, many others come not as immigrants but as exiles. Exile is fundamentally different from immigration. The immigrant chooses, perhaps under duress, to make a new home in a new land, but the exile refuses to settle in a new country—instead devoutly waiting to return to the place they call home. By not assimilating, the exile protects and nurtures the dream of return. Sometimes it is a dream that never comes true, and they die in a country that never became their home. But in other cases political climates change and return becomes possible. Extremely rarely, an exile actually plays a role in helping their country gain its freedom, thereby creating the very conditions that allow them to return.

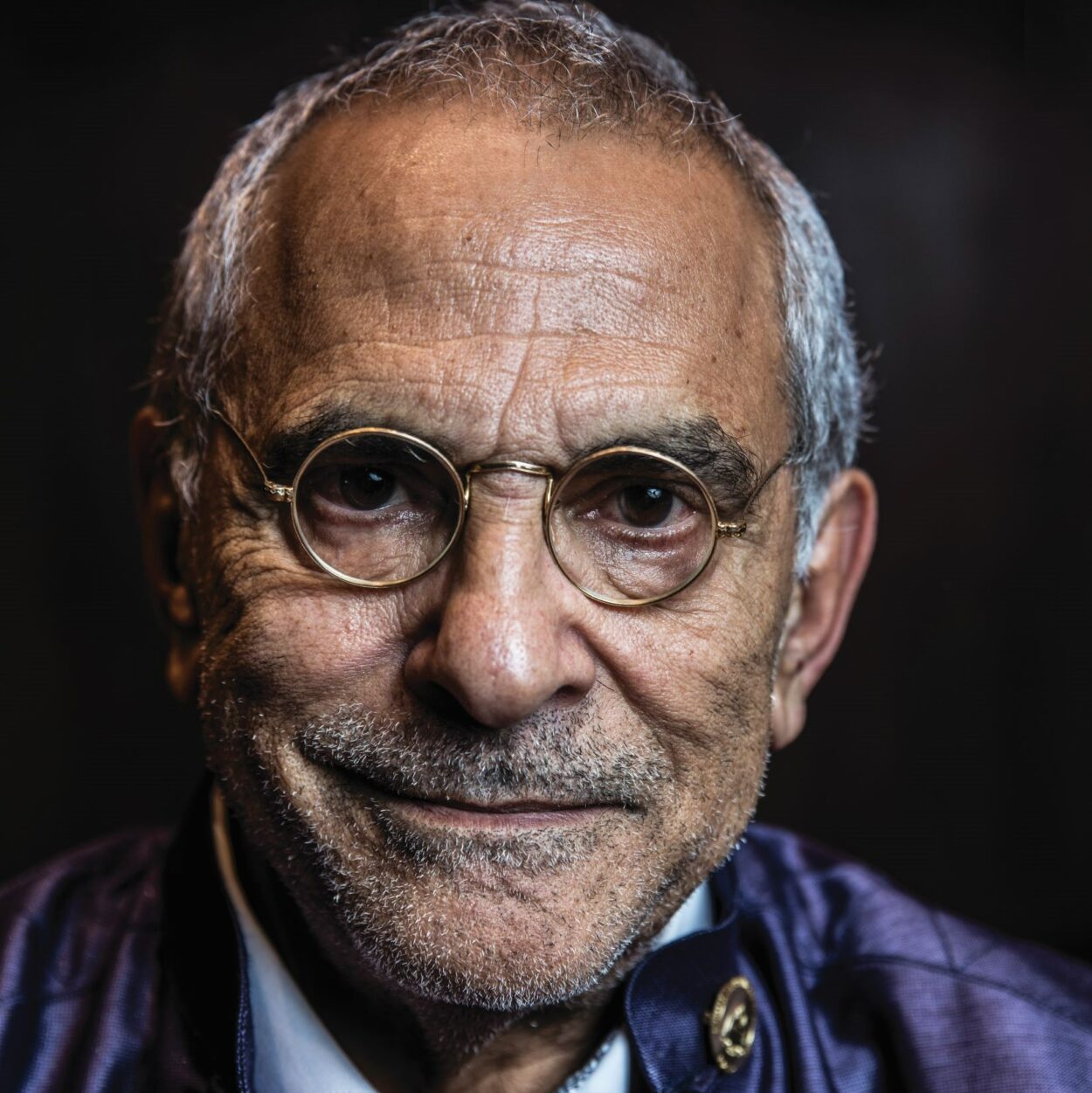

Such is the story of José Ramos-Horta ’84 (Antioch University, MA in Peace Studies). A devoted advocate for his home country of Timor-Leste (formerly East Timor), he kept true to his people throughout 24 years of political exile in the US. During the time he couldn’t return to his home country, he stayed busy: pleading his nation’s case before the UN, studying at Antioch and Harvard, and even, in 1996, winning the Nobel Peace Prize. Everything he did was in service to his country’s freedom—a freedom that Timor-Leste finally gained at the turn of the millenium.

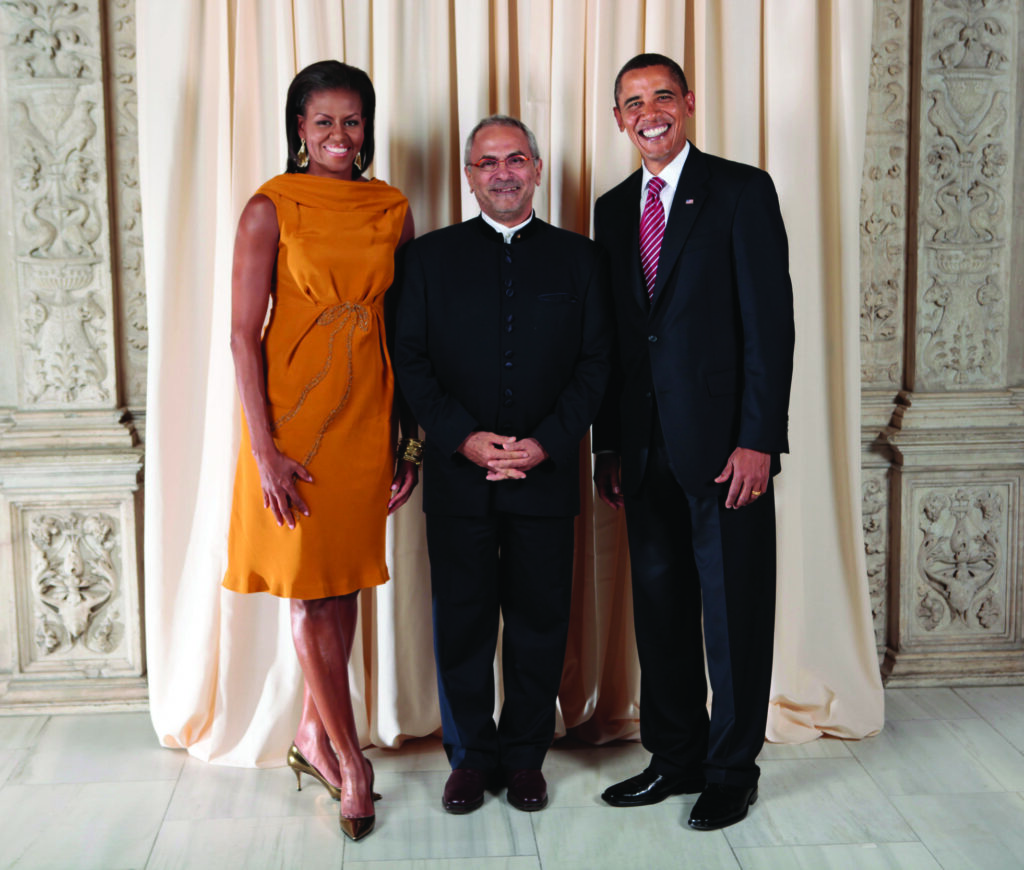

Ramos-Horta has lived in Timor-Leste’s capital of Dili ever since, in the home he began designing and working to build almost as soon as he returned to his homeland. It was in Dili that he served as Timor-Leste’s second president, from 2007-2012. And this fall it was from his home there that he consented to an email interview in which he told me about his time at Antioch, his struggle for his people, and his dreams of freedom, peace, and self-determination for all the peoples of the world. His is a story fit for a movie (and indeed Oscar Isaac played him in 2009’s Balibo), but it is more than anything the story of a man who never forgot his home.

I. A Nation Colonized, Then Occupied

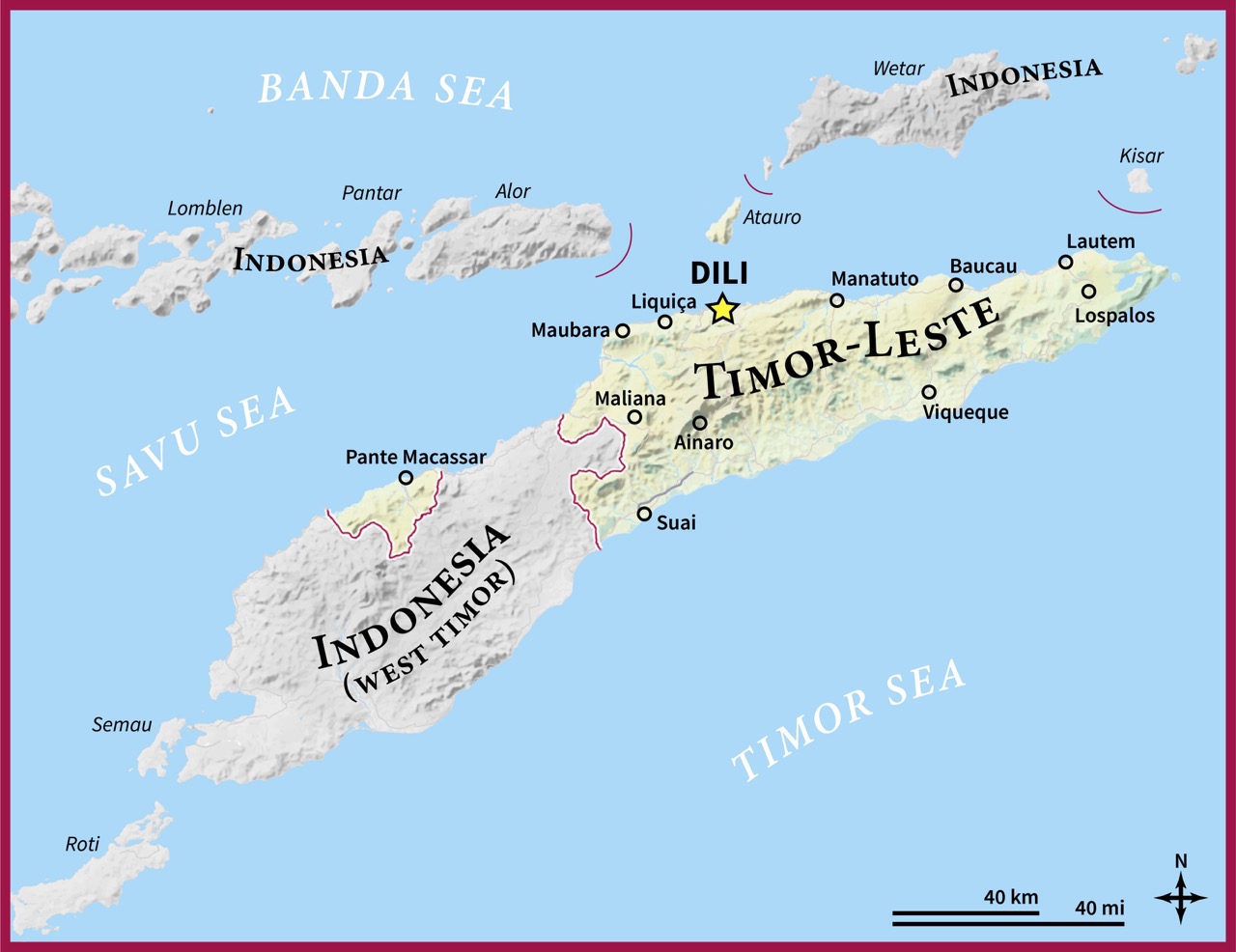

In order to understand Ramos-Horta’s story, it’s necessary to understand the story of the country he has spent his life advocating for. Timor-Leste primarily comprises the eastern half Timor, (which itself means “east” in Malay), an island that lies about 300 miles north of Australia. Humans have been living on present-day Timor-Leste for at least 40,000 years. In 1515 CE, Portuguese traders landed on Timor, and they soon began treating it as a colony (later the Dutch colonized the western half of the island). As part of the Portuguese Empire, along with countries as distant as Macau, Mozambique, and Brazil, Timor-Leste faced resource extraction, violent oppression, and foreign rule. This was the empire into which Ramos-Horta was born in 1949.

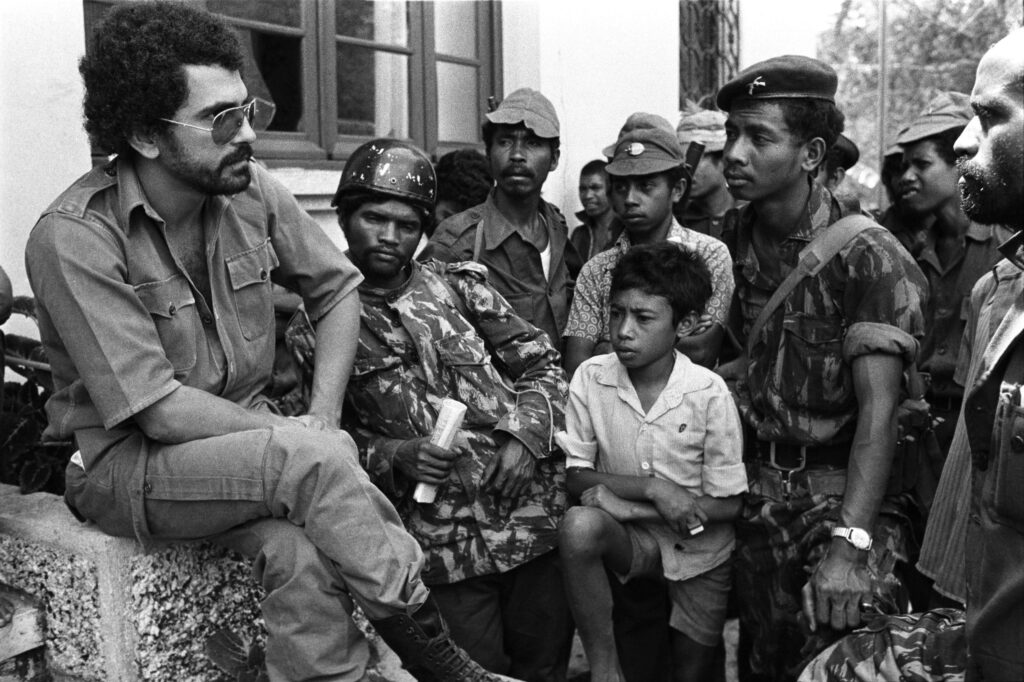

A natural leader, by his early twenties Ramos-Horta was working to raise political consciousness against the Portuguese colonizers. This led those very colonial administrators to exile him for two years to Portuguese East Africa. But he returned in 1971, and he continued to be politically active, helping to start the socialist independence party Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin).

In 1974, the “Carnation Revolution” in Portugal led to rapid decolonization, and within a year the Portuguese largely abandoned Timor-Leste. When Fretilin declared the country’s independence as the Democratic Republic of East Timor, Ramos-Horta was appointed Foreign Minister.

The independent state lasted only ten days before its giant neighbor Indonesia invaded. But there was some forewarning, and just three days before the invasion the government sent Ramos-Horta to New York, to petition the UN to intervene. It was no use; the nations of the world could not be convinced to save this fledgling country. In fact quite the opposite: Indonesia’s invasion began just hours after a state visit from US President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who offered military support to its dictator Suharto. Regarding Timor-Leste, Kissinger told the dictator, “It is important that whatever you do succeeds quickly.”

The invasion was swift, but Indonesia’s occupation stretched out for decades, comprising a campaign of oppression, destruction, and mass killing. “Over 200,000 people—children, women, elderly—have died in a country of 700,000 inhabitants,” wrote Ramos-Horta nine years later, in his Antioch Master’s Thesis. It was, he said, “one of the world’s greatest tragedies in modern times,” and yet no one with the power to stop it seemed to even know it was happening, let alone care to stop it. He would make it his work to change that.

II. Building Community in Exile

Ramos-Horta arrived in the US with very little money and only a few possessions. In the years that followed, he lived partly on the generosity of friends he made, partly through journalistic work, and partly on the ability to live cheaply. “I lived in many different places in Manhattan,” he says. “Mostly in very rundown sublets, cockroach-infested units.”

But it’s not the bad places he remembers most. Instead it’s the generosity of people like his “friend, Afro-American filmmaker [and] attorney Robert Van Lierop, who so graciously opened his old brownstone home to me.” In this Harlem home and its surrounding neighborhood, remembers Ramos-Horta, “I felt at home, safe, relaxed, happy.” Another time, a Portuguese friend, Isaura Praça, rented him her beautiful apartment at the edge of Spanish Harlem and the Upper East Side “for a fraction of the real rent.”

However nice the apartments were, though, the important thing to Ramos-Horta was living in a world capital with access to people and institutions. Over his decades of exile, Ramos-Horta stayed busy. He traveled all over the globe, helping organize events and conferences, studying global politics, and learning the ins and outs of the UN, which is headquartered just east of Manhattan’s Midtown. Ultimately, he found that the “UN is mostly a global forum, a very important one, but not really the one that determines the course of events, solutions.” That power, he found, was often concentrated in Washington, DC, “a truly global capital of real power.” He ended up traveling to DC often and even lived there for a year, in an apartment close to Capitol Hill.

Probably the most important thing Ramos-Horta did in his time of exile was make friends. For instance, one summer he was in Europe, and he traveled to the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy, to meet with Noam Chomsky, the famous linguist, political theorist, and critic of American empire. Ramos-Horta found the famous academic “wearing jeans, very casual, his feet on the desk.” As he explains, Chomsky “received me very warmly and promptly accepted my invitation to him to speak at an international solidarity conference to be held in Lisbon some few weeks later.” This was the beginning of a friendship that included learning on both sides.

Chomsky became an outspoken critic of Indonesia’s bloody occupation of Timor-Leste and the US role in providing arms and support to it, writing in 1994 that it was “perhaps the greatest death toll relative to population since the Holocaust.” Ramos-Horta learned from Chomsky about what he describes as “the other side of US politics, society, the cynical mercantile interests driving US foreign policy.”

At the same time, Ramos-Horta’s great desire to understand all sides of issues led him to seek out other teachers. He took a course at Columbia University with Zbigniew Brzezinski, the “famed Cold Warrior” as Ramos-Horta puts it, who had served as National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter.

“What I learned in life was not to be an idealogue, dogmatic,” says Ramos-Horta. He learned “to always try to hear [and] see other views.” So he saw that while Chomsky “was [and] has been very right about the wrongs, failings, the darker sides of US establishment … [In] the US Congress and any Administration there have been, there were, great people who were and are the best side of American idealism.”

III. A Scholar of Peace

It was an abiding desire to deepen what he was learning through his advocacy and professional connections that led Ramos-Horta to Antioch University. He applied to the Master of Arts in Individualized Study, where he ended up creating a course of study truly individualized to his own interests: an MA in Peace Studies. These studies would help Ramos-Horta develop a complex, nuanced framework for considering the future of Timor-Leste.

He enrolled, he says, “because that is what I wanted to do, something of use for my work and advocacy for my country.” He wanted to research conflict in general—and specifically to look into the root causes of Timor-Leste’s conflict with Indonesia. And he wanted to look for solutions.

One of the program’s requirements is that students identify scholars in their chosen field who become their mentors and support their studies. “I was extremely fortunate to have had the best possible Faculty Committee,” says Ramos-Horta. He recruited Columbia University’s Professor of Islamic and Southeast Asian History William Roff; Francesc Vendrell, who was then one of the UN’s senior political affairs officers specializing in International Human Rights Law; Rutgers professor and international human rights lawyer Roger S. Clark; and the linguist and social critic Noam Chomsky. These scholars “were friends of mine, very supportive of what I was doing,” says Ramos-Horta—but now that he was in this program, he got to embark for two years as their formal student.

He explains that he met regularly with his committee members. Roff, Vendrell, and Clark lived near Ramos-Horta in New York City, and every month he took the bus to Boston to meet up with Chomsky, who he describes as “such a generous, kind man.”

Ramos-Horta ended up titling his master’s thesis “East Timor: A Case Study in International Law.” In it he strove to explore two fundamental questions: the right of all colonized people to self-determination under both the UN’s Charter and International Law, and “the violation of these principles by Indonesia.” The thesis is partly an attempt to collect the recent history of his home country, partly a dive into the relevant law, and partly a reflection on “the dilemma of small nations everywhere—their struggle for survival in a world marred by economic, political, ideological, and military competition….” When he finished it, the thesis was 180 pages long—he had answered some of his questions and more than fulfilled the requirements of the degree.

The degree did not of course make an immediate difference in his country’s fate. “I would not say that studying for this degree opened doors at the UN or anywhere,” says Ramos-Horta. But it did give him the opportunity, flexibility, and supervision to dive into researching questions that had long fascinated and troubled him. These became deeply-researched chapters like “Self-Defense and the Use of Force,” “Kissinger, the Globalist, and the Fate of a Small Nation,” and “The Case of East Timor and Human Rights Law.” As Ramos-Horta explains, “The MA in Peace Studies led me to research and learn more on conflict, its sources, root causes, and solutions.”

IV. “Our Society Will Not Be Based on Revenge”

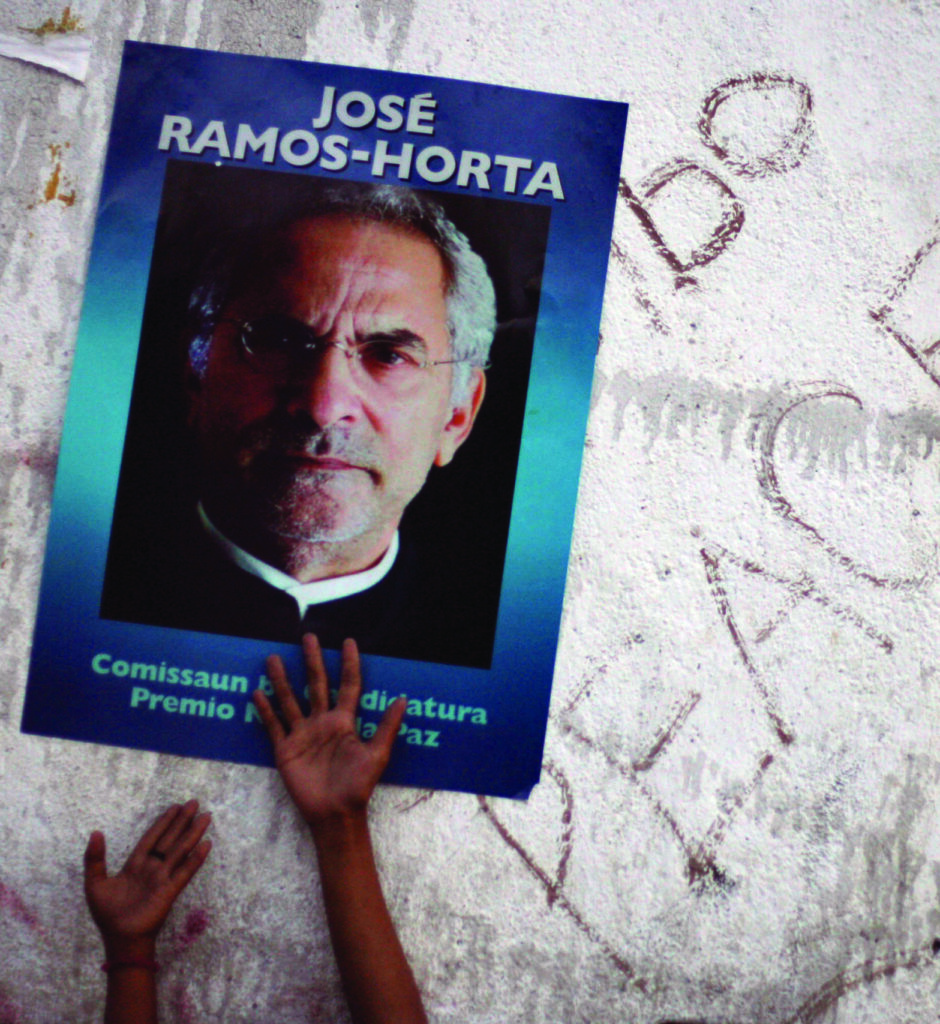

In the dozen years after completing his degree at Antioch, Ramos- Horta continued advocating for his country. He also continued his studies, attending the Executive Leadership Program at Harvard’s Kennedy School and becoming a Senior Associate Member of St. Antony’s College at the University of Oxford. His long exile stretched into its third decade. And then, in 1996, a committee in Oslo awarded Ramos-Horta, along with his countryman Bishop Carlos Felipe Ximenes Belo, the Nobel Peace Prize.

This prize trained a giant spotlight on the plight of Timor-Leste. For more than two decades Ramos-Horta had been working to educate the world of his country’s plight and create political pressure to end Indonesia’s occupation. Now the Nobel, overnight, made tremendous progress on this goal.

It also gave him a chance to give a Nobel Lecture. On December 10, 1996, Ramos-Horta delivered a speech on this prominent stage, building on his decades of research and thought—including the work he did in his Antioch MA in Peace Studies.

In the lecture, he shares his country’s history with the world, lays out the moral and legal case for Timor-Leste’s right to self-determination, and explains the commonality of his cause with those of other colonized or otherwise oppressed peoples, from “the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh, Bougainville, Kurdistan, Sri Lanka, India, Tibet, Chechnya, Ogoni, [to] West Papua”—places where “millions of people seek to assert their most fundamental rights.” At the end, he lays out a roadmap to accomplishing peaceful independence for Timor-Leste.

Perhaps the most radical and prescient part of his lecture is towards the end. This is where he explains that his people’s intention is not to form a tribunal and prosecute the crimes of the departing regime and its collaborators. “Our society will not be based on revenge,” he writes, and he assures those East Timorese who were serving in the Indonesian administration of the country, those serving as security forces, and the police that they should “not fear an independent East Timor.” In fact, he says, “their full active involvement in running the country will be necessary to ensure a smooth transition.”

To this day, Ramos-Horta advocates for reconciliation, in contrast with the principle of No Justice, No Peace. “Yes, we must respect those who have died during a conflict,” he said just this October in an address at Expo 2020, “but it’s more important to address the future of those alive. We must learn lessons from the atrocities that took place, so that we can prevent a recurrence.”

V. Return

Three years after laying out a path to peace in his Nobel Lecture, Ramos-Horta got a chance to put all of that in practice when Indonesia permitted a binding independence referendum be administered in Timor-Leste. The Timorese resoundingly chose to form their own nation, and in December 1999 Ramos-Horta moved back home, ending his 24 years of political exile. Just as he had left only three days before Indonesia’s invasion in 1975, now he returned mere weeks after its withdrawal.

He carried back with him all that he had learned in his 24 years of exile. This served him and his country well, as he worked closely with the UN Transitional Authority in East Timor to help lay the foundations for the new nation’s government. And when the first elections were held in 2002, the new administration appointed him to be Timor-Leste’s Foreign Minister. He once again officially held this role that he’d been appointed to 27 years earlier by a government that only lasted ten days—though throughout his decades exile he had continued performing many of the duties of a foreign minister, if unofficially.

In 2007 Ramos-Horta ran for President of Timor-Leste and won with 67% of the vote. This role offered an entirely new way to give back to this country to whose birth as an independent nation he had given his life’s work. He survived an assassination attempt in 2008 and worked throughout his term to reduce poverty and to build diplomatic ties with neighboring countries and other allies.

In 2012, after losing his campaign for re-election, Ramos-Horta conceded and stepped down from the Presidency. But he has stayed busy. A year after leaving politics, he was appointed UN Special Envoy to Guinea Bissau in West Africa, working to restore constitutional rule in this fellow lusophone country. Beyond that, he works with many organizations and causes, gives frequent speeches, and has even released a book collecting his speeches and writings: Words of Hope in Troubled Times.

Ramos-Horta has lived an impactful enough life to merit a long biography. In that volume, his time at Antioch might be little more than a footnote or part of a chapter. In this, if not in much else, he is like so many other Antiochians—a passionate person who was drawn to study at an institution that shared many of his values, who used the school as a platform to develop some key skills, and who has continued to embody those values over the years since graduating.

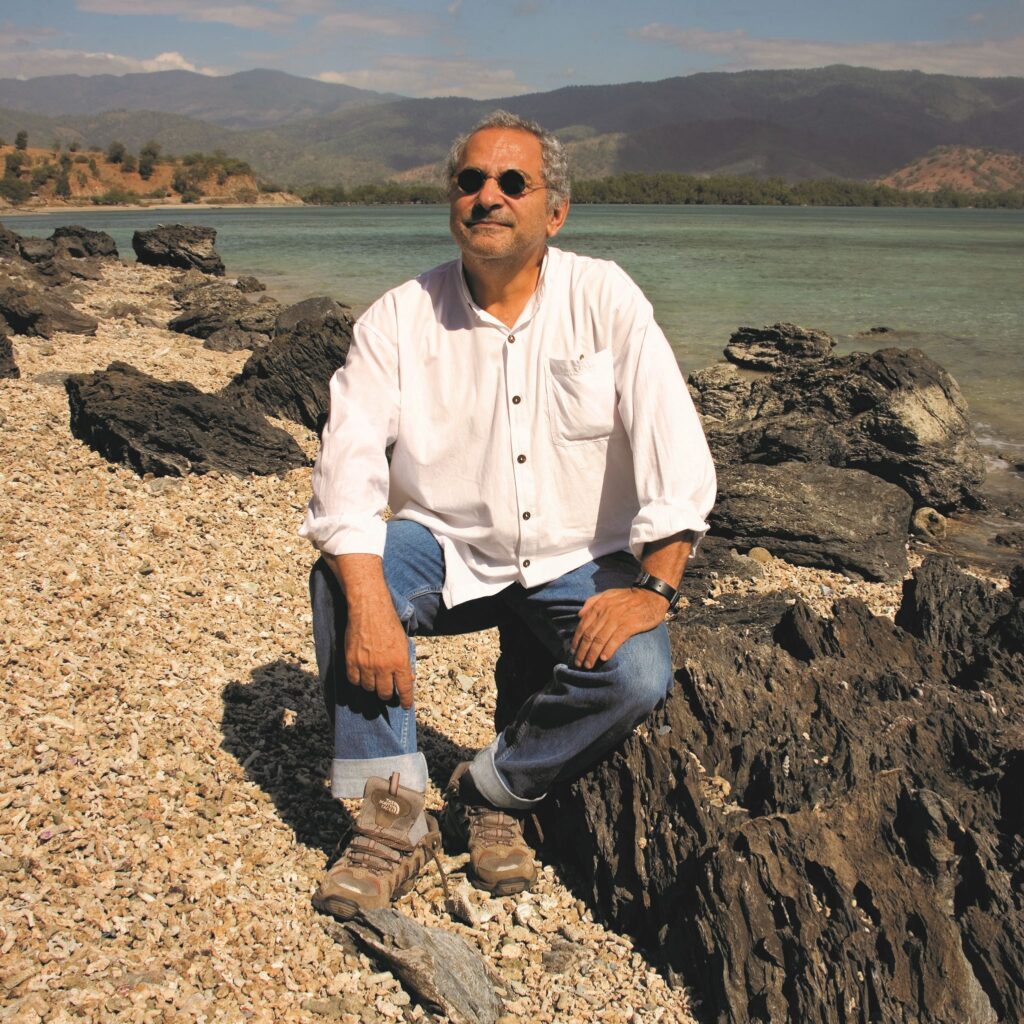

Today, Ramos-Horta lives in the same house in Dili that he began building as soon as he returned in 1999. He describes it as “a house that I designed, improvised, over several years, no engineers or architect involved, traditional style, tropical.” In 2001 he expanded the lot it sits on by buying a neighboring parcel, back when land could be purchased “so so cheaply.” He planted a small forest there, where it had been barren land, and now “lots of birds make a living here, where they have food.”

The longtime exile sounds at peace as he describes the home he has made over the last 22 years. He makes sure there is water for the birds and also for the bigger animals who live there, with whom he’s on a first-name basis. “I have a couple of female deer, Bambi and Bambina,” he says. And then there are a “few cats, who are illegal squatters. They are not mine. They just sneaked in, procreate, and more cats appeared.” Soon he will have lived there, on the edge of his little forest, for longer than he was forced to stay away.